Leverage dbt to generate analytics and ML-ready pipelines with SQL and Python with Snowflake

Introduction

The focus of this workshop will be to demonstrate how we can use both SQL and python together in the same workflow to run both analytics and machine learning models on dbt.

All code in today’s workshop can be found on GitHub.

What you'll use during the lab

- A Snowflake account with ACCOUNTADMIN access

- A dbt account

What you'll learn

- How to build scalable data transformation pipelines using dbt, and Snowflake using SQL and Python

- How to leverage copying data into Snowflake from a public S3 bucket

What you need to know

- Basic to intermediate SQL and python.

- Basic understanding of dbt fundamentals. We recommend the dbt Fundamentals course if you're interested.

- High level machine learning process (encoding, training, testing)

- Simple ML algorithms — we will use logistic regression to keep the focus on the workflow, not algorithms!

What you'll build

- A set of data analytics and prediction pipelines using Formula 1 data leveraging dbt and Snowflake, making use of best practices like data quality tests and code promotion between environments

- We will create insights for:

- Finding the lap time average and rolling average through the years (is it generally trending up or down)?

- Which constructor has the fastest pit stops in 2021?

- Predicting the position of each driver given using a decade of data (2010 - 2020)

As inputs, we are going to leverage Formula 1 datasets hosted on a dbt Labs public S3 bucket. We will create a Snowflake Stage for our CSV files then use Snowflake’s COPY INTO function to copy the data in from our CSV files into tables. The Formula 1 is available on Kaggle. The data is originally compiled from the Ergast Developer API.

Overall we are going to set up the environments, build scalable pipelines in dbt, establish data tests, and promote code to production.

Configure Snowflake

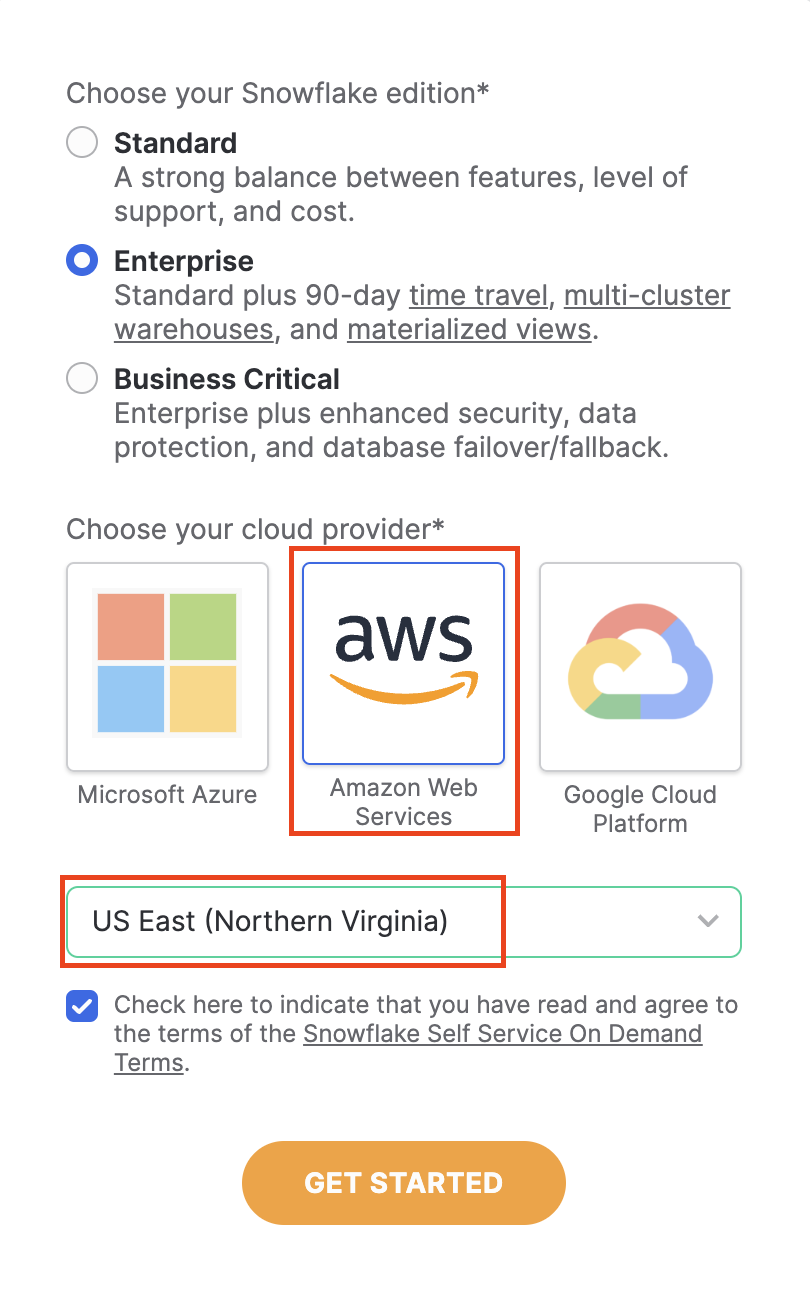

- Log in to your trial Snowflake account. You can sign up for a Snowflake Trial Account using this form if you don’t have one.

- Ensure that your account is set up using AWS in the US East (N. Virginia). We will be copying the data from a public AWS S3 bucket hosted by dbt Labs in the us-east-1 region. By ensuring our Snowflake environment setup matches our bucket region, we avoid any multi-region data copy and retrieval latency issues.

-

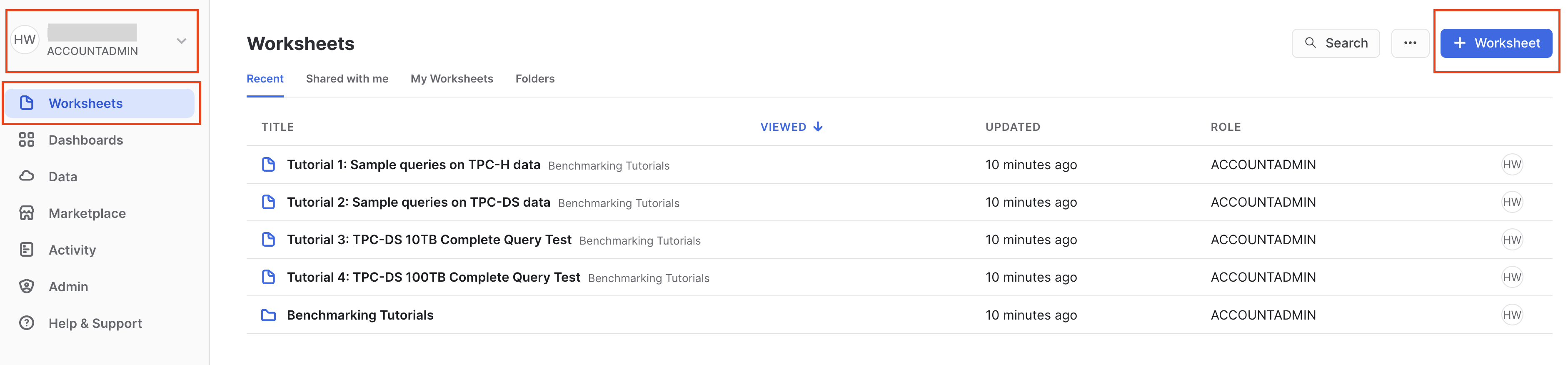

After creating your account and verifying it from your sign-up email, Snowflake will direct you back to the UI called Snowsight.

-

When Snowsight first opens, your window should look like the following, with you logged in as the ACCOUNTADMIN with demo worksheets open:

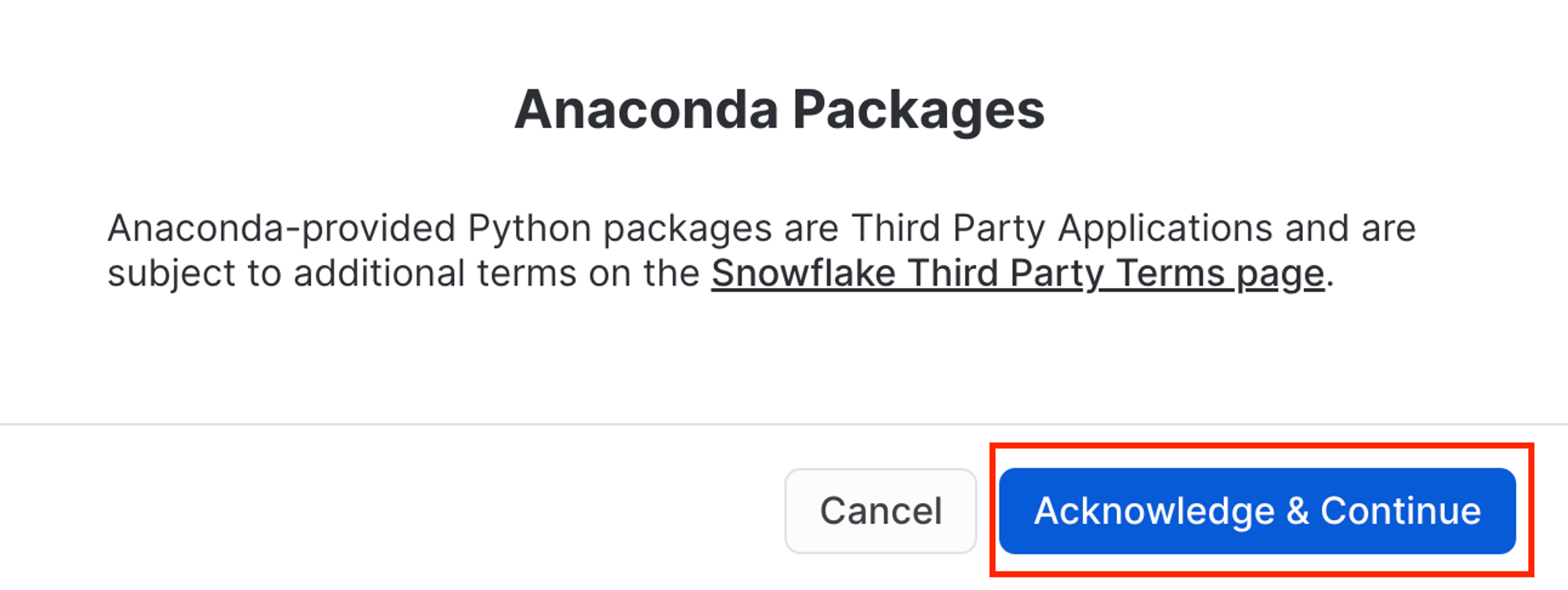

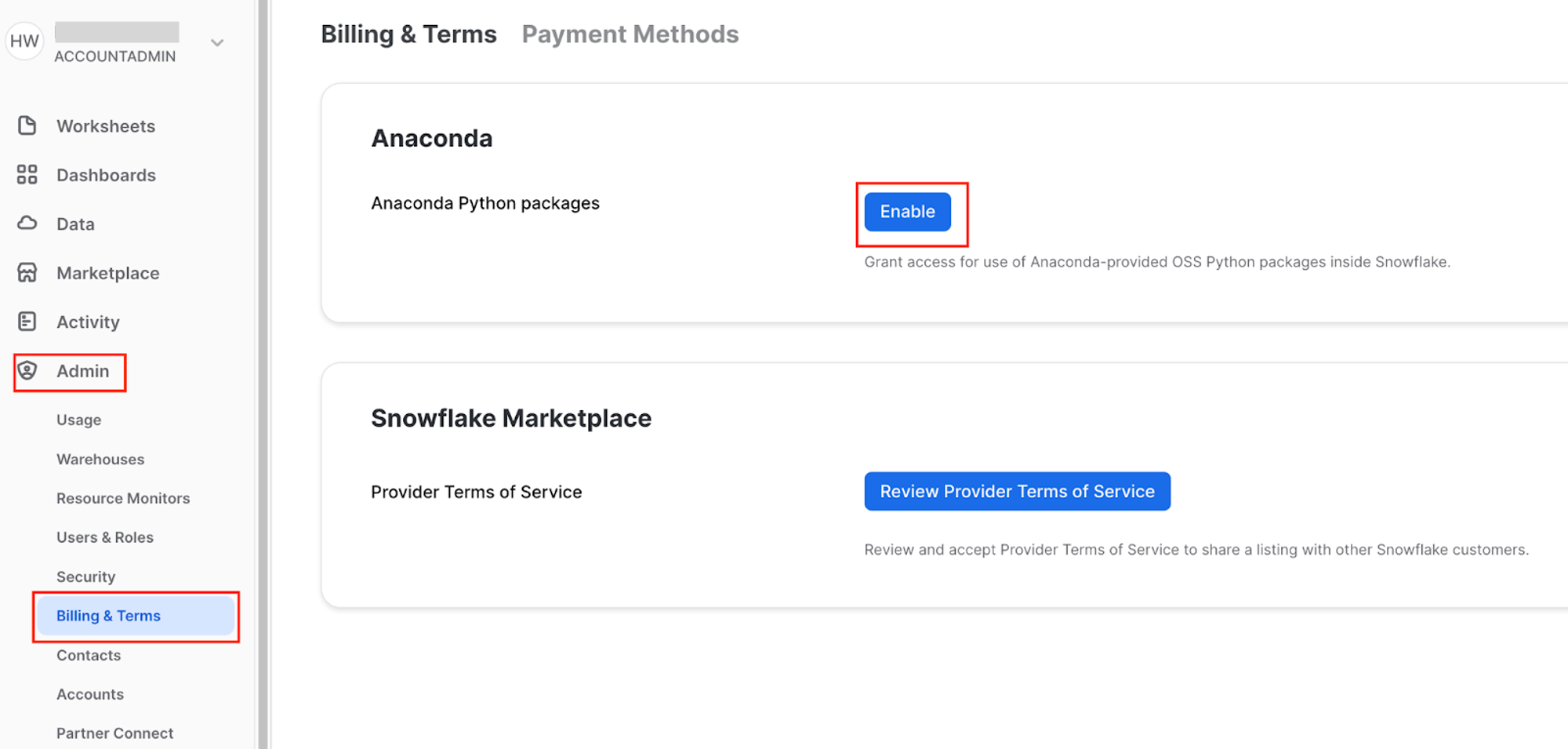

- Navigate to Admin > Billing & Terms. Click Enable > Acknowledge & Continue to enable Anaconda Python Packages to run in Snowflake.

- Finally, create a new Worksheet by selecting + Worksheet in the upper right corner.

Connect to data source

We need to obtain our data source by copying our Formula 1 data into Snowflake tables from a public S3 bucket that dbt Labs hosts.

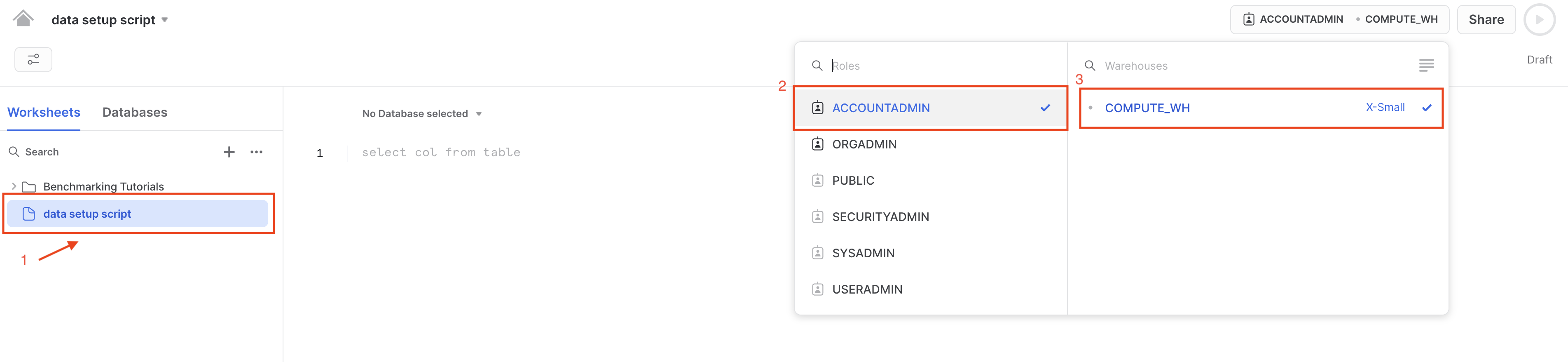

-

When a new Snowflake account is created, there should be a preconfigured warehouse in your account named

COMPUTE_WH. -

If for any reason your account doesn’t have this warehouse, we can create a warehouse using the following script:

create or replace warehouse COMPUTE_WH with warehouse_size=XSMALL -

Rename the worksheet to

data setup scriptsince we will be placing code in this worksheet to ingest the Formula 1 data. Make sure you are still logged in as the ACCOUNTADMIN and select the COMPUTE_WH warehouse. -

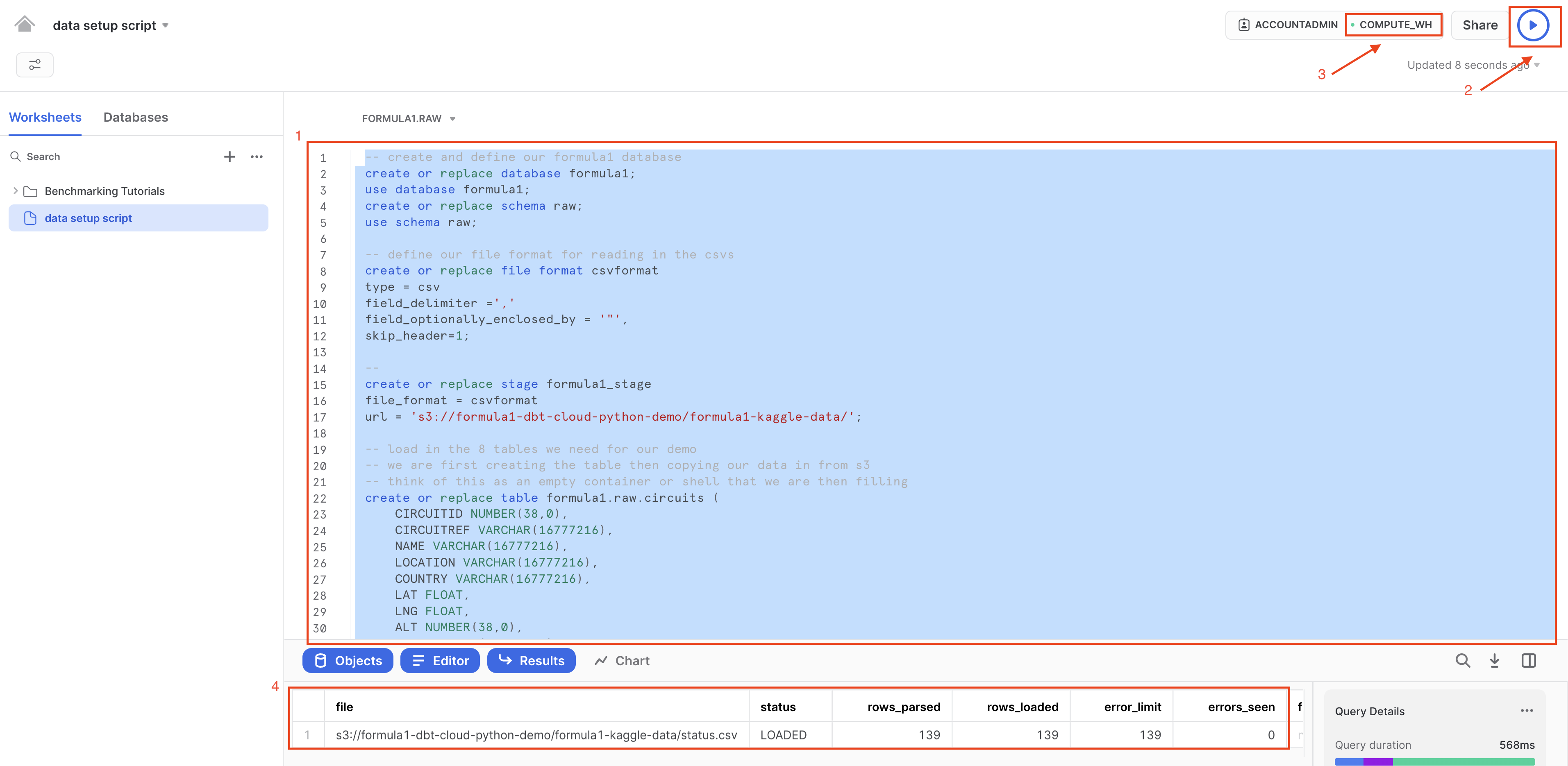

Copy the following code into the main body of the Snowflake worksheet. You can also find this setup script under the

setupfolder in the Git repository. The script is long since it's bring in all of the data we'll need today!-- create and define our formula1 database

create or replace database formula1;

use database formula1;

create or replace schema raw;

use schema raw;

-- define our file format for reading in the CSVs

create or replace file format CSVformat

type = CSV

field_delimiter =','

field_optionally_enclosed_by = '"',

skip_header=1;

--

create or replace stage formula1_stage

file_format = CSVformat

url = 's3://formula1-dbt-cloud-python-demo/formula1-kaggle-data/';

-- load in the 8 tables we need for our demo

-- we are first creating the table then copying our data in from s3

-- think of this as an empty container or shell that we are then filling

create or replace table formula1.raw.circuits (

CIRCUITID NUMBER(38,0),

CIRCUITREF VARCHAR(16777216),

NAME VARCHAR(16777216),

LOCATION VARCHAR(16777216),

COUNTRY VARCHAR(16777216),

LAT FLOAT,

LNG FLOAT,

ALT NUMBER(38,0),

URL VARCHAR(16777216)

);

-- copy our data from public s3 bucket into our tables

copy into circuits

from @formula1_stage/circuits.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.constructors (

CONSTRUCTORID NUMBER(38,0),

CONSTRUCTORREF VARCHAR(16777216),

NAME VARCHAR(16777216),

NATIONALITY VARCHAR(16777216),

URL VARCHAR(16777216)

);

copy into constructors

from @formula1_stage/constructors.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.drivers (

DRIVERID NUMBER(38,0),

DRIVERREF VARCHAR(16777216),

NUMBER VARCHAR(16777216),

CODE VARCHAR(16777216),

FORENAME VARCHAR(16777216),

SURNAME VARCHAR(16777216),

DOB DATE,

NATIONALITY VARCHAR(16777216),

URL VARCHAR(16777216)

);

copy into drivers

from @formula1_stage/drivers.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.lap_times (

RACEID NUMBER(38,0),

DRIVERID NUMBER(38,0),

LAP NUMBER(38,0),

POSITION FLOAT,

TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

MILLISECONDS NUMBER(38,0)

);

copy into lap_times

from @formula1_stage/lap_times.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.pit_stops (

RACEID NUMBER(38,0),

DRIVERID NUMBER(38,0),

STOP NUMBER(38,0),

LAP NUMBER(38,0),

TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

DURATION VARCHAR(16777216),

MILLISECONDS NUMBER(38,0)

);

copy into pit_stops

from @formula1_stage/pit_stops.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.races (

RACEID NUMBER(38,0),

YEAR NUMBER(38,0),

ROUND NUMBER(38,0),

CIRCUITID NUMBER(38,0),

NAME VARCHAR(16777216),

DATE DATE,

TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

URL VARCHAR(16777216),

FP1_DATE VARCHAR(16777216),

FP1_TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

FP2_DATE VARCHAR(16777216),

FP2_TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

FP3_DATE VARCHAR(16777216),

FP3_TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

QUALI_DATE VARCHAR(16777216),

QUALI_TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

SPRINT_DATE VARCHAR(16777216),

SPRINT_TIME VARCHAR(16777216)

);

copy into races

from @formula1_stage/races.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.results (

RESULTID NUMBER(38,0),

RACEID NUMBER(38,0),

DRIVERID NUMBER(38,0),

CONSTRUCTORID NUMBER(38,0),

NUMBER NUMBER(38,0),

GRID NUMBER(38,0),

POSITION FLOAT,

POSITIONTEXT VARCHAR(16777216),

POSITIONORDER NUMBER(38,0),

POINTS NUMBER(38,0),

LAPS NUMBER(38,0),

TIME VARCHAR(16777216),

MILLISECONDS NUMBER(38,0),

FASTESTLAP NUMBER(38,0),

RANK NUMBER(38,0),

FASTESTLAPTIME VARCHAR(16777216),

FASTESTLAPSPEED FLOAT,

STATUSID NUMBER(38,0)

);

copy into results

from @formula1_stage/results.csv

on_error='continue';

create or replace table formula1.raw.status (

STATUSID NUMBER(38,0),

STATUS VARCHAR(16777216)

);

copy into status

from @formula1_stage/status.csv

on_error='continue'; -

Ensure all the commands are selected before running the query — an easy way to do this is to use Ctrl-a to highlight all of the code in the worksheet. Select run (blue triangle icon). Notice how the dot next to your COMPUTE_WH turns from gray to green as you run the query. The status table is the final table of all 8 tables loaded in.

-

Let’s unpack that pretty long query we ran into component parts. We ran this query to load in our 8 Formula 1 tables from a public S3 bucket. To do this, we:

- Created a new database called

formula1and a schema calledrawto place our raw (untransformed) data into. - Defined our file format for our CSV files. Importantly, here we use a parameter called

field_optionally_enclosed_by =since the string columns in our Formula 1 CSV files use quotes. Quotes are used around string values to avoid parsing issues where commas,and new lines/nin data values could cause data loading errors. - Created a stage to locate our data we are going to load in. Snowflake Stages are locations where data files are stored. Stages are used to both load and unload data to and from Snowflake locations. Here we are using an external stage, by referencing an S3 bucket.

- Created our tables for our data to be copied into. These are empty tables with the column name and data type. Think of this as creating an empty container that the data will then fill into.

- Used the

copy intostatement for each of our tables. We reference our staged location we created and upon loading errors continue to load in the rest of the data. You should not have data loading errors but if you do, those rows will be skipped and Snowflake will tell you which rows caused errors

- Created a new database called

-

Now let's take a look at some of our cool Formula 1 data we just loaded up!

-

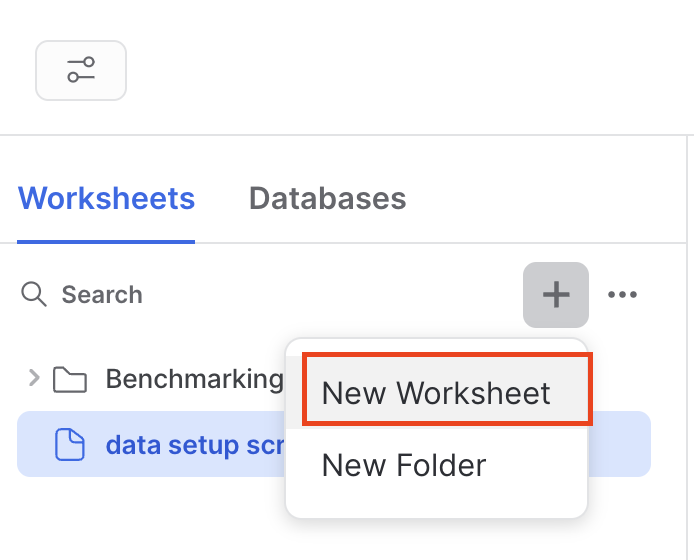

Create a new worksheet by selecting the + then New Worksheet.

-

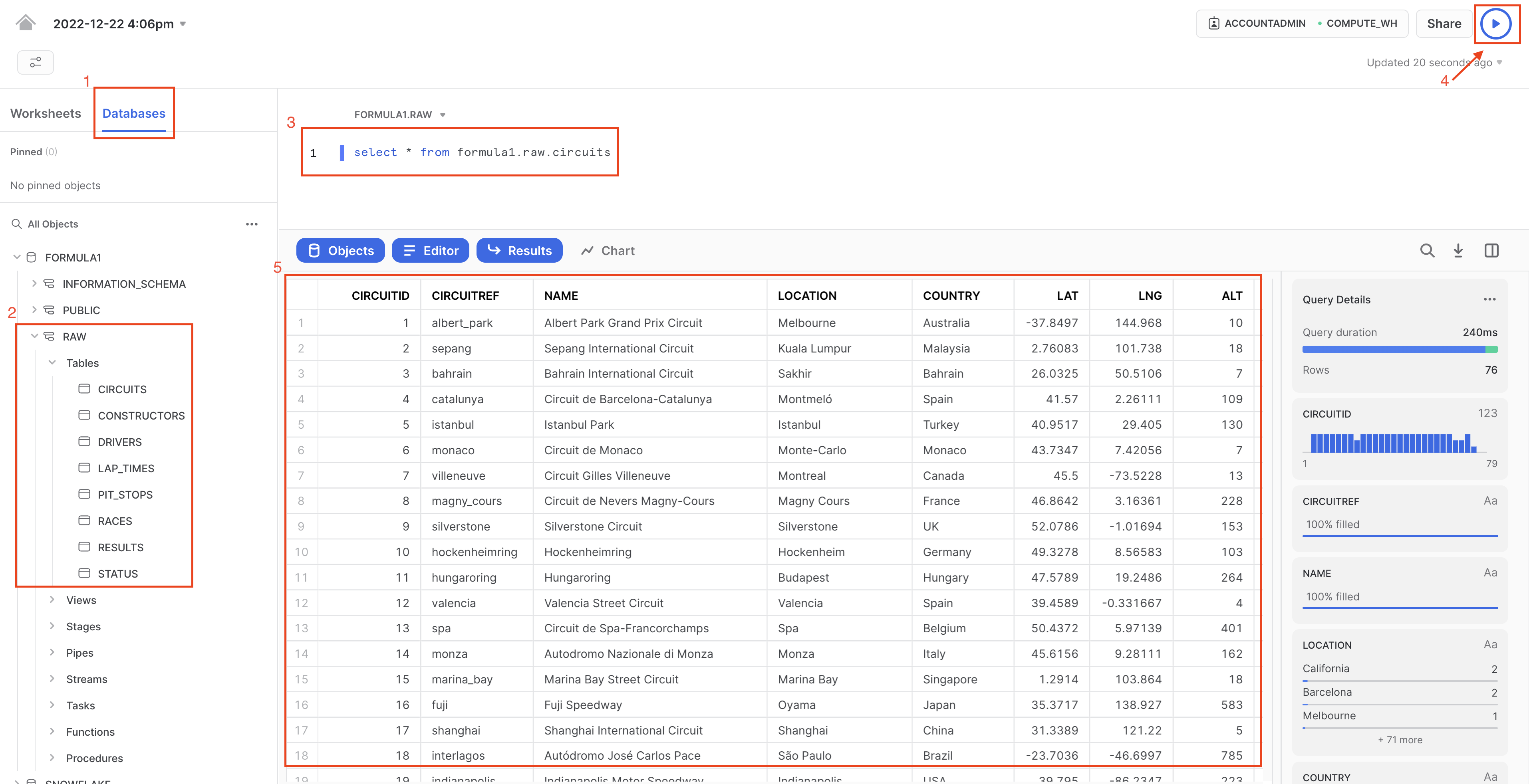

Navigate to Database > Formula1 > RAW > Tables.

-

Query the data using the following code. There are only 76 rows in the circuits table, so we don’t need to worry about limiting the amount of data we query.

select * from formula1.raw.circuits -

Run the query. From here on out, we’ll use the keyboard shortcuts Command-Enter or Control-Enter to run queries and won’t explicitly call out this step.

-

Review the query results, you should see information about Formula 1 circuits, starting with Albert Park in Australia!

-

Finally, ensure you have all 8 tables starting with

CIRCUITSand ending withSTATUS. Now we are ready to connect into dbt!

-

Configure dbt

-

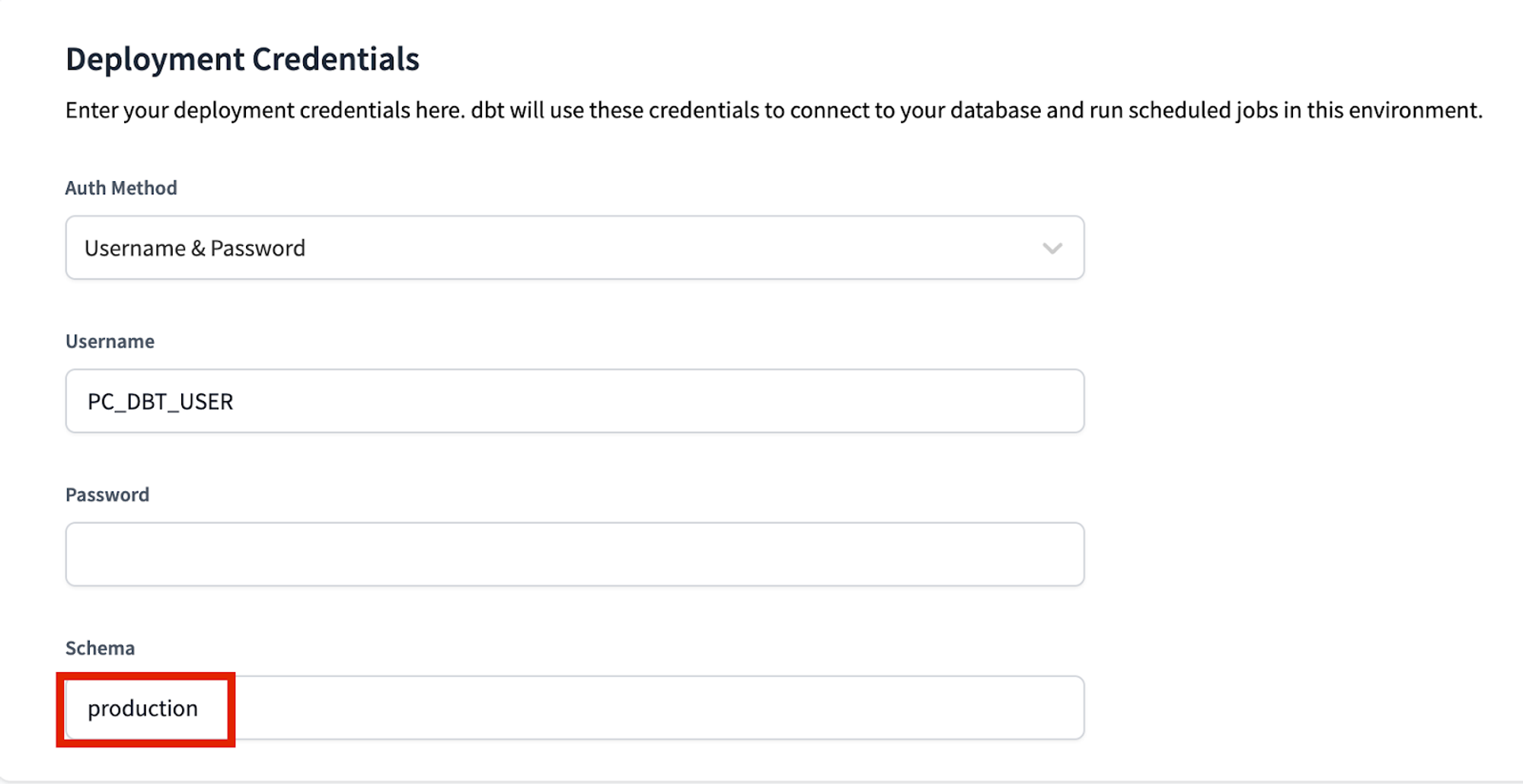

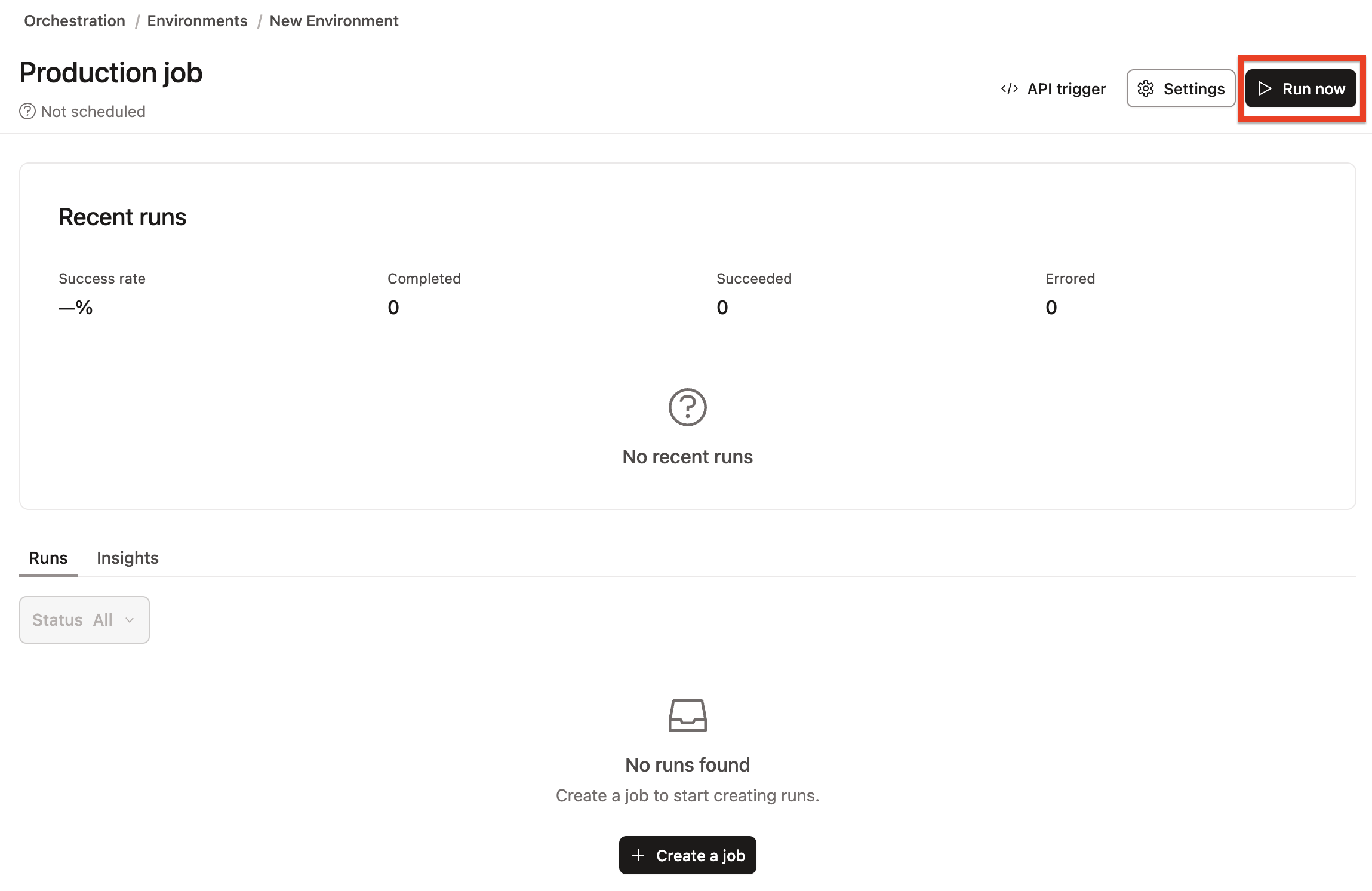

We are going to be using Snowflake Partner Connect to set up a dbt account. Using this method will allow you to spin up a fully fledged dbt account with your Snowflake connection, managed repository, environments, and credentials already established.

-

Navigate out of your worksheet back by selecting home.

-

In Snowsight, confirm that you are using the ACCOUNTADMIN role.

-

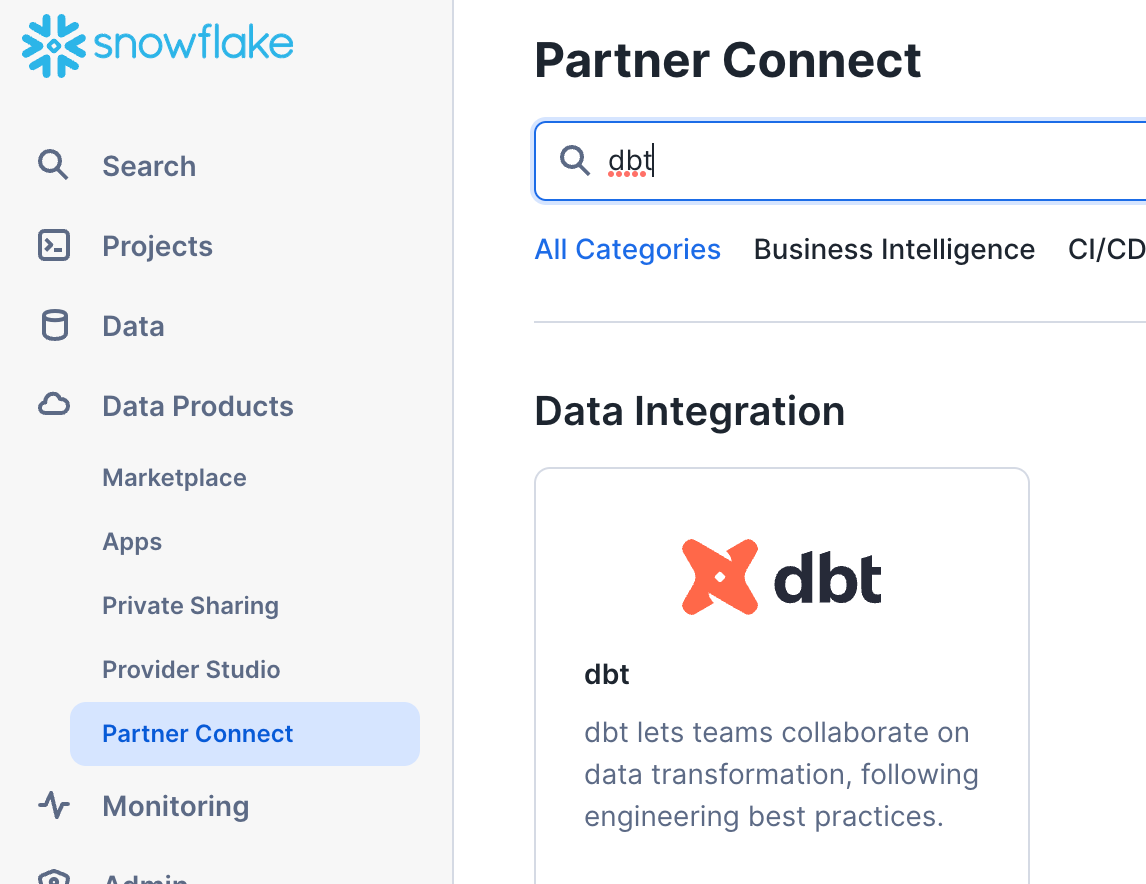

Navigate to the Data Products > Partner Connect. Find dbt either by using the search bar or navigating the Data Integration. Select the dbt tile.

-

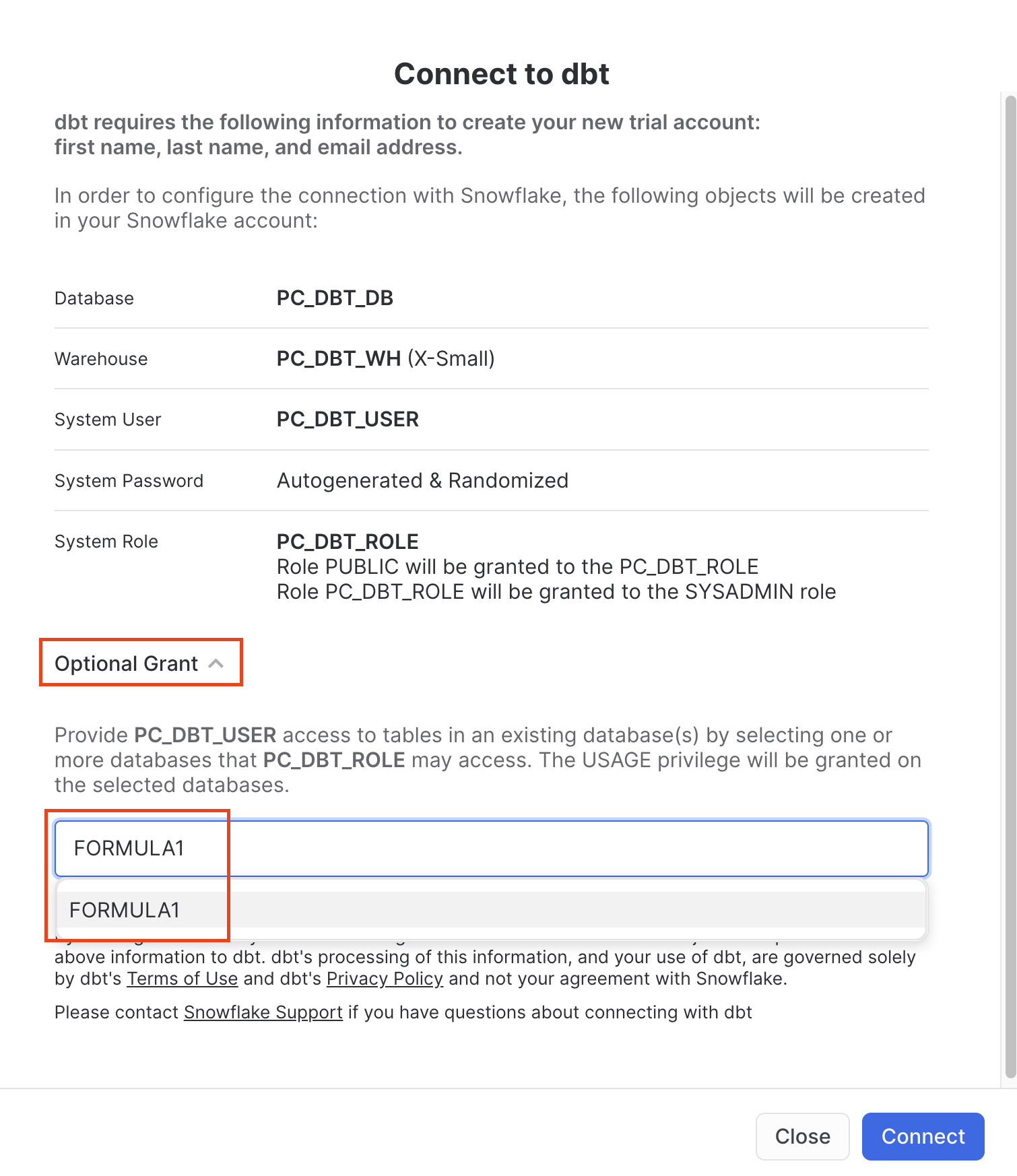

You should now see a new window that says Connect to dbt. Select Optional Grant and add the

FORMULA1database. This will grant access for your new dbt user role to the FORMULA1 database. -

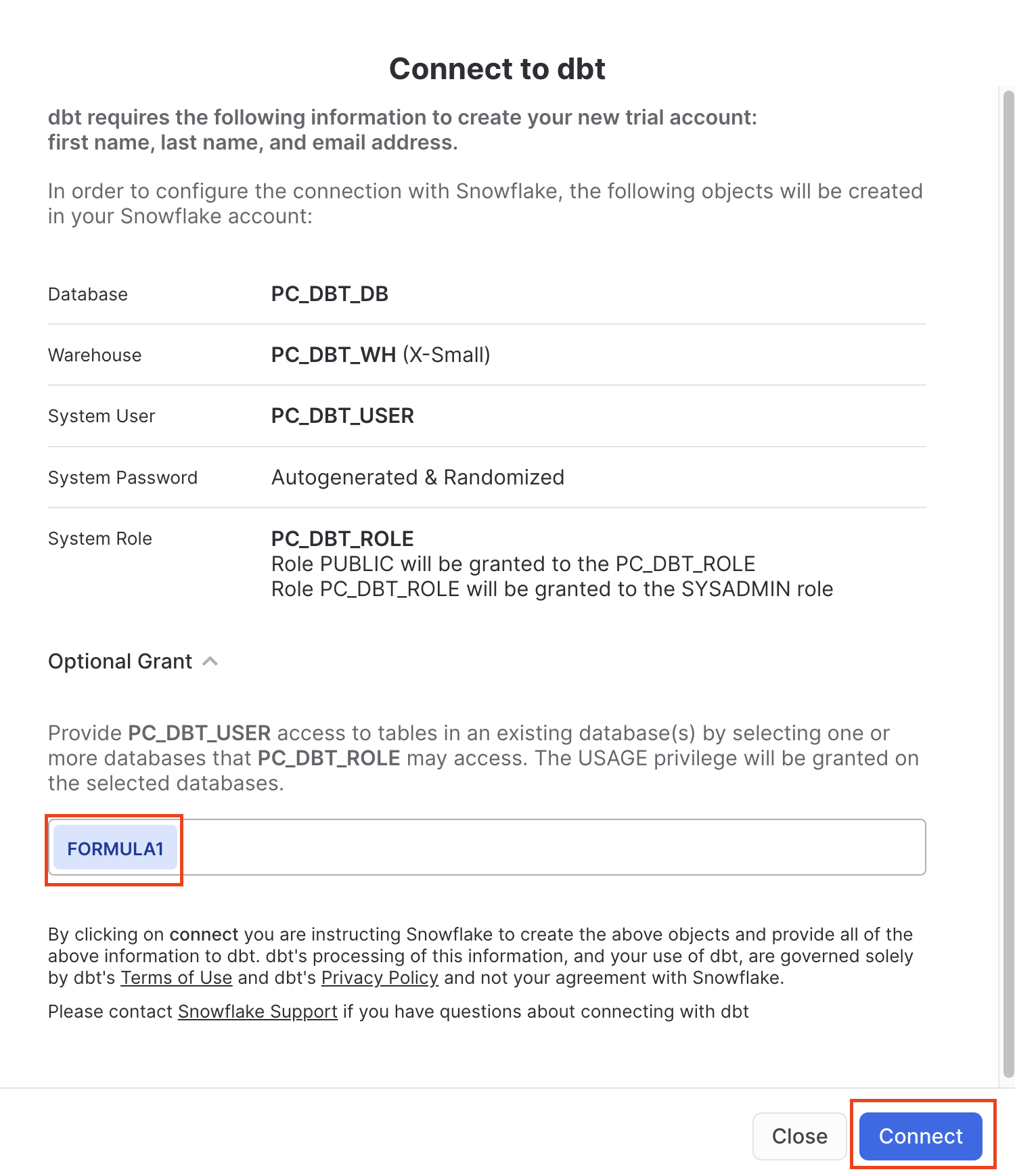

Ensure the

FORMULA1is present in your optional grant before clicking Connect. This will create a dedicated dbt user, database, warehouse, and role for your dbt trial. -

When you see the Your partner account has been created window, click Activate.

-

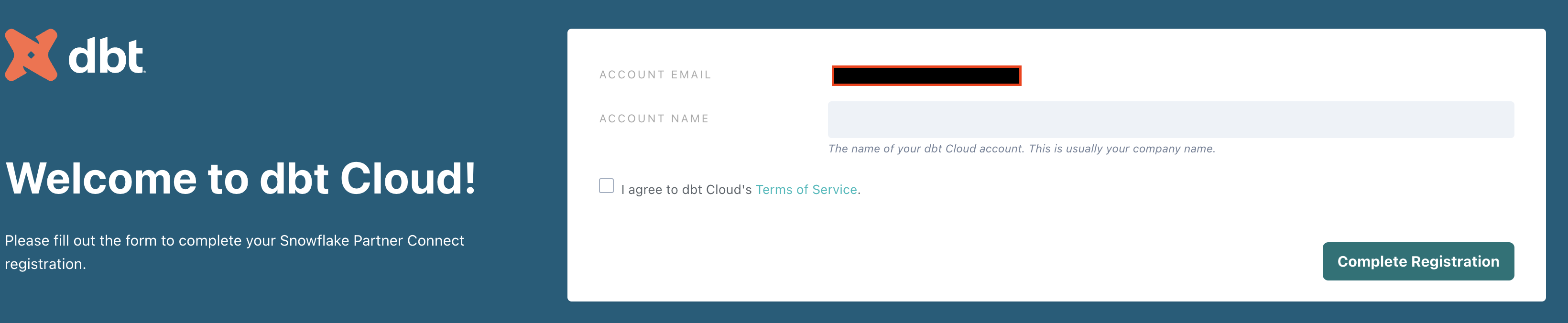

You should be redirected to a dbt registration page. Fill out the form. Make sure to save the password somewhere for login in the future.

-

Select Complete Registration. You should now be redirected to your dbt account, complete with a connection to your Snowflake account, a deployment and a development environment, and a sample job.

-

To help you version control your dbt project, we have connected it to a managed repository, which means that dbt Labs will be hosting your repository for you. This will give you access to a Git workflow without you having to create and host the repository yourself. You will not need to know Git for this workshop; dbt will help guide you through the workflow. In the future, when you’re developing your own project, feel free to use your own repository. This will allow you to learn more about features like Slim CI builds after this workshop.

Change development schema name and navigate the IDE

-

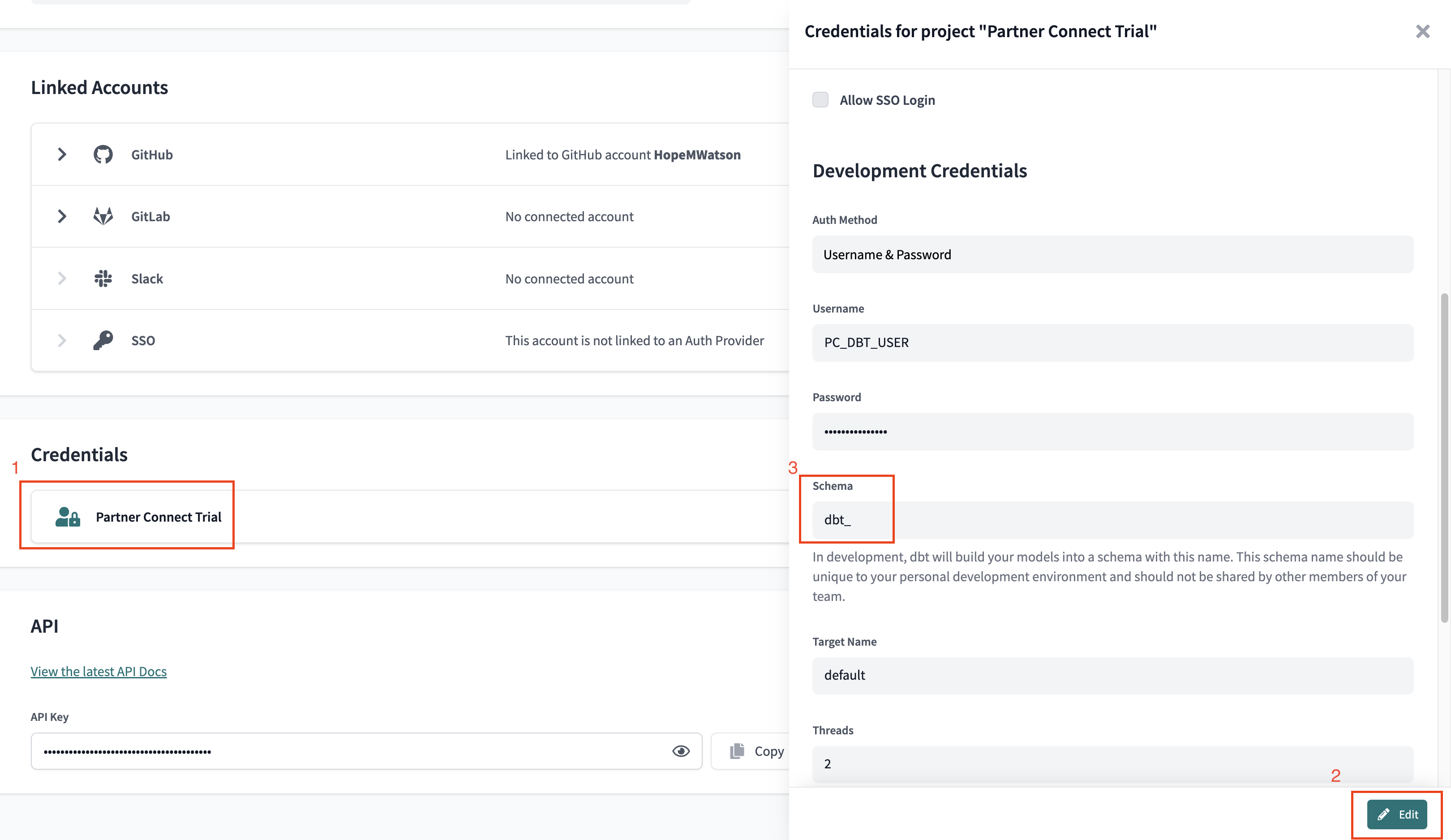

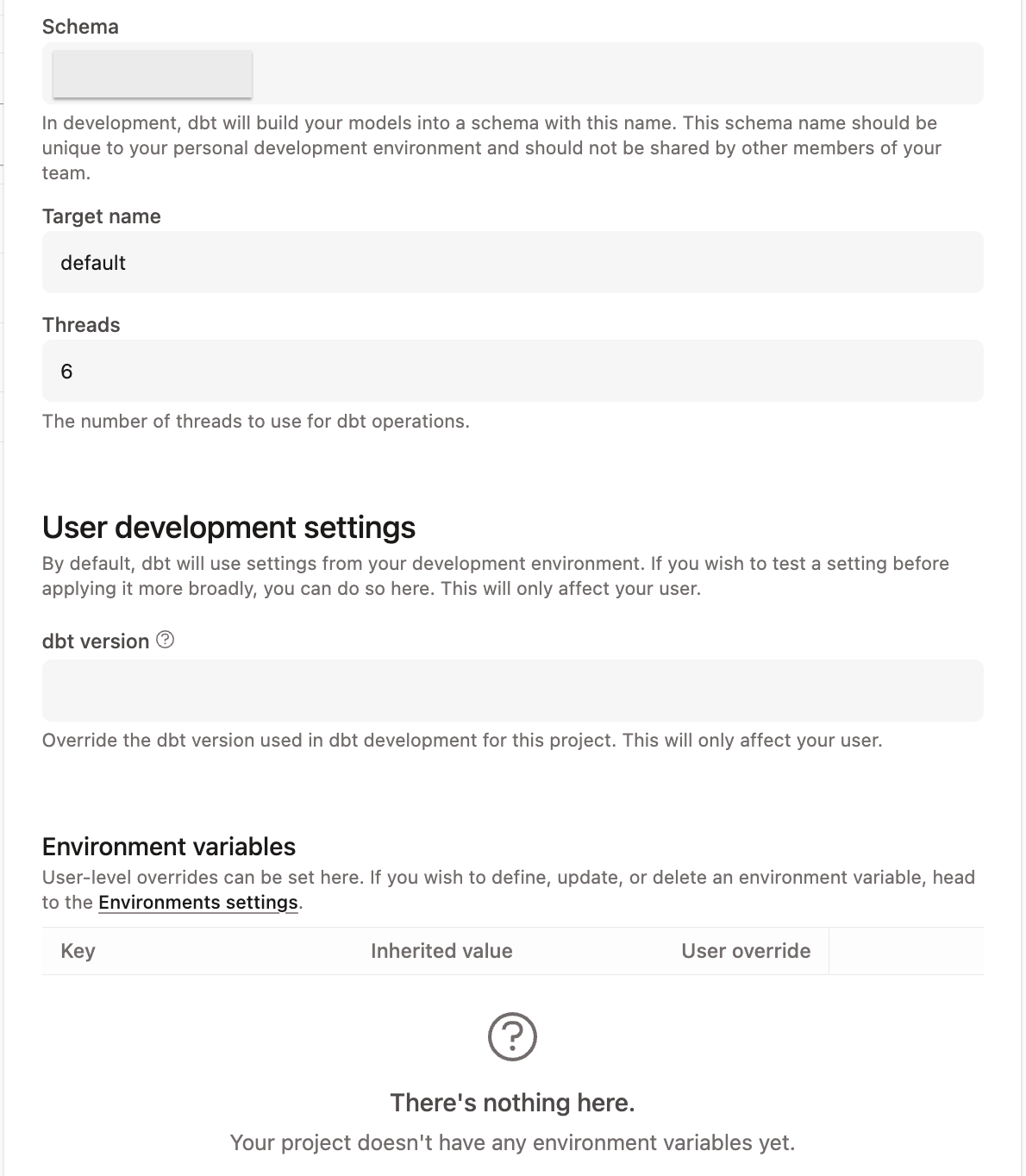

First we are going to change the name of our default schema to where our dbt models will build. By default, the name is

dbt_. We will change this todbt_<YOUR_NAME>to create your own personal development schema. To do this, click on your account name in the left side menu and select Account settings. -

Navigate to the Credentials menu and select Partner Connect Trial, which will expand the credentials menu.

-

Click Edit and change the name of your schema from

dbt_todbt_YOUR_NAMEreplacingYOUR_NAMEwith your initials and name. Be sure to click Save for your changes! -

We now have our own personal development schema, amazing! When we run our first dbt models they will build into this schema.

-

Let’s open up dbt’s Integrated Development Environment (Studio IDE) and familiarize ourselves. Choose Develop at the top of the UI.

-

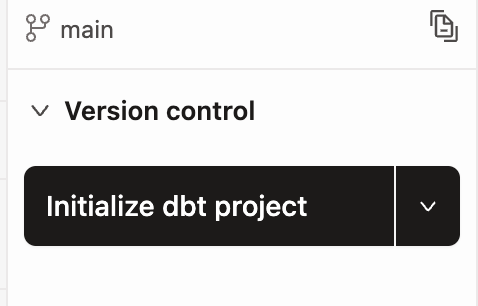

When the Studio IDE is done loading, click Initialize dbt project. The initialization process creates a collection of files and folders necessary to run your dbt project.

-

After the initialization is finished, you can view the files and folders in the file tree menu. As we move through the workshop we'll be sure to touch on a few key files and folders that we'll work with to build out our project.

-

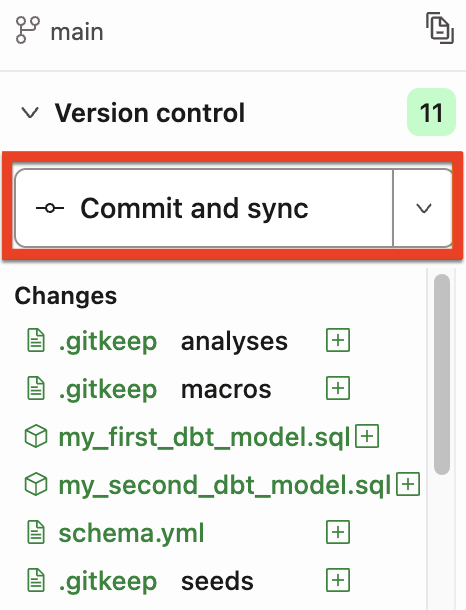

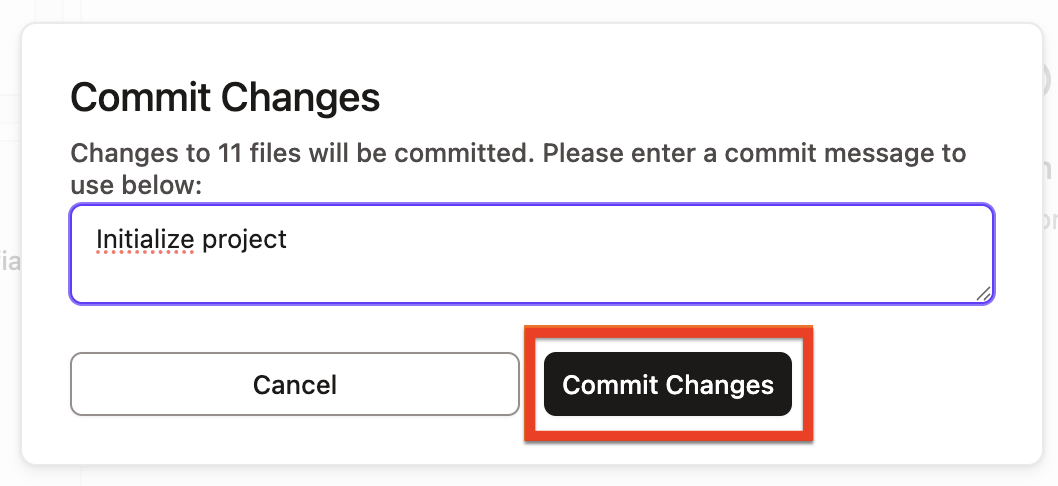

Next click Commit and sync to commit the new files and folders from the initialize step. We always want our commit messages to be relevant to the work we're committing, so be sure to provide a message like

initialize projectand select Commit Changes. -

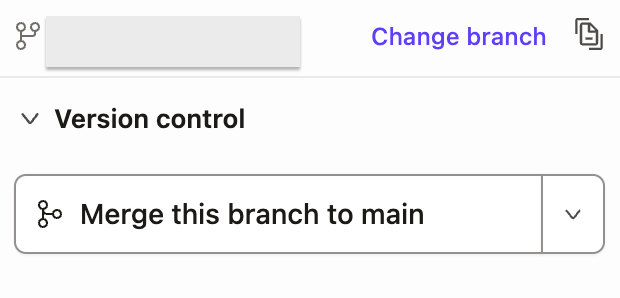

Committing your work here will save it to the managed git repository that was created during the Partner Connect signup. This initial commit is the only commit that will be made directly to our

mainbranch and from here on out we'll be doing all of our work on a development branch. This allows us to keep our development work separate from our production code. -

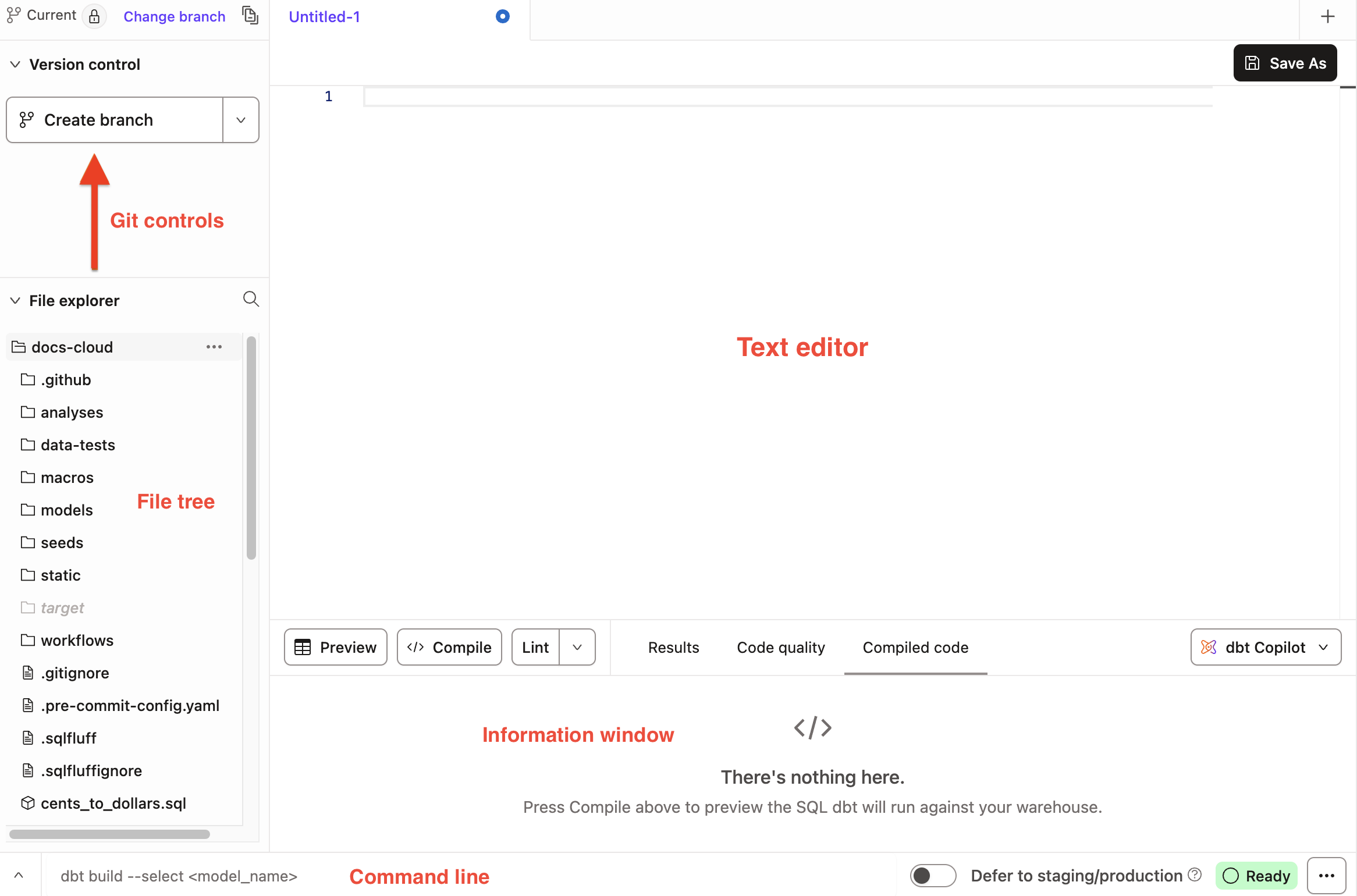

There are a couple of key features to point out about the Studio IDE before we get to work. It is a text editor, an SQL and Python runner, and a CLI with Git version control all baked into one package! This allows you to focus on editing your SQL and Python files, previewing the results with the SQL runner (it even runs Jinja!), and building models at the command line without having to move between different applications. The Git workflow in dbt allows both Git beginners and experts alike to be able to easily version control all of their work with a couple clicks.

-

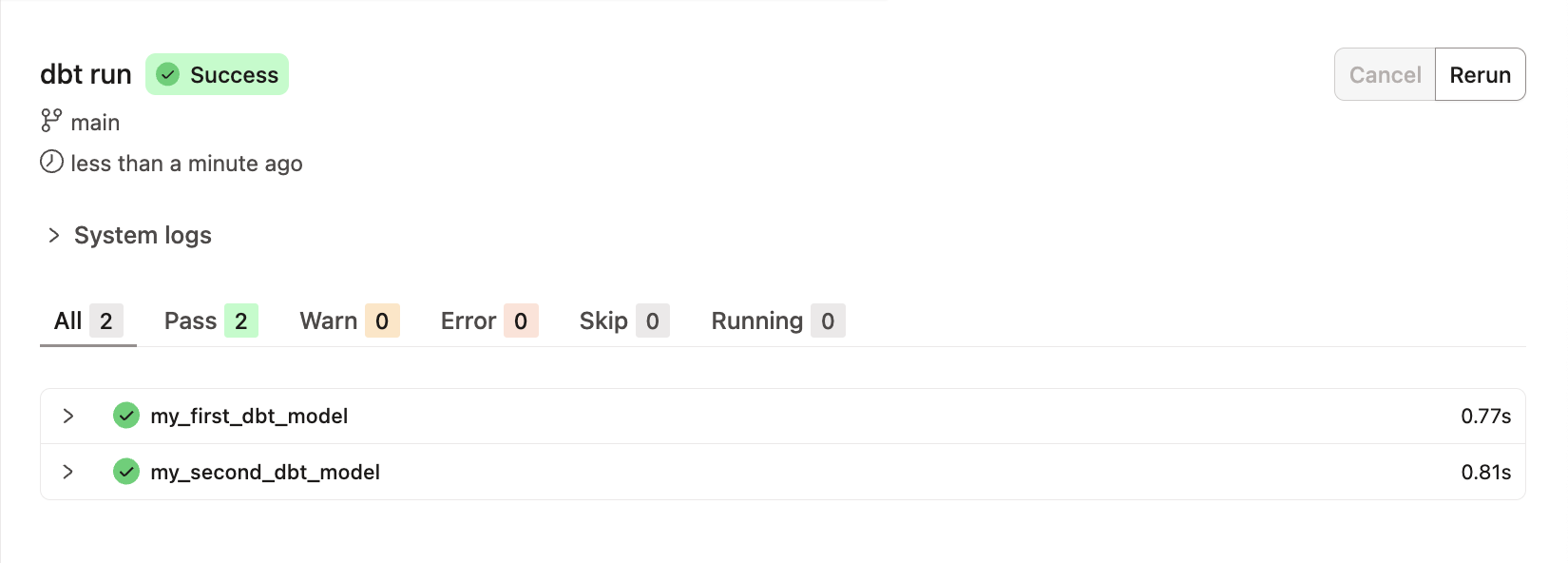

Let's run our first dbt models! Two example models are included in your dbt project in the

models/examplesfolder that we can use to illustrate how to run dbt at the command line. Typedbt runinto the command line and click Enter on your keyboard. When the run bar expands you'll be able to see the results of the run, where you should see the run complete successfully. -

The run results allow you to see the code that dbt compiles and sends to Snowflake for execution. To view the logs for this run, select one of the model tabs using the > icon and then Details. If you scroll down a bit you'll be able to see the compiled code and how dbt interacts with Snowflake. Given that this run took place in our development environment, the models were created in your development schema.

-

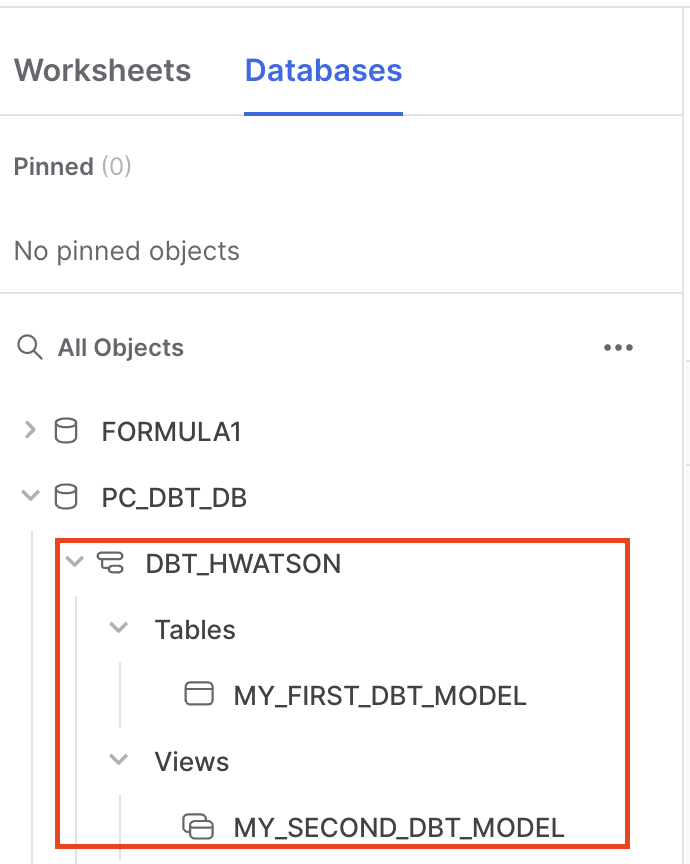

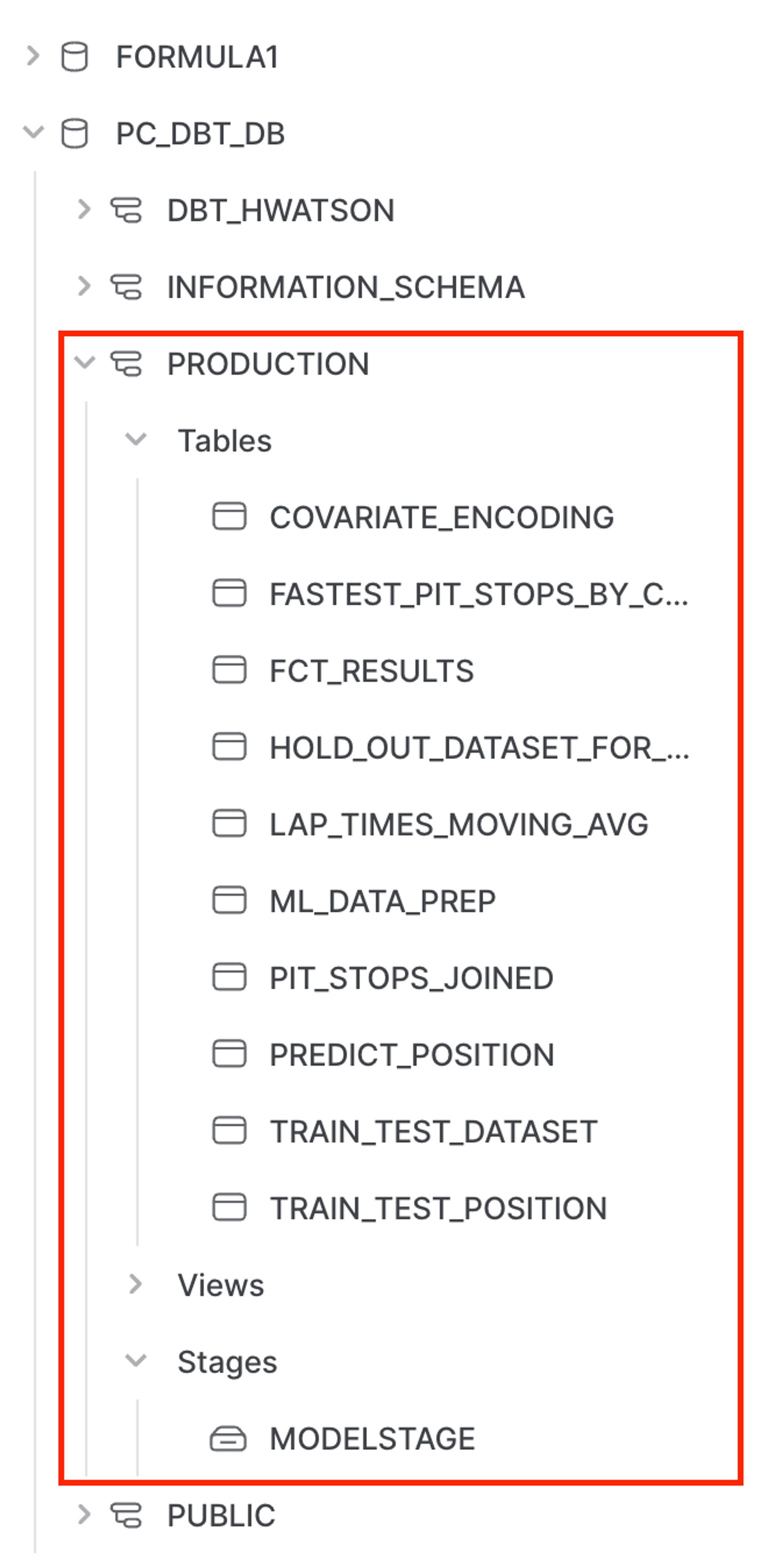

Now let's switch over to Snowflake to confirm that the objects were actually created. Click on the three dots … above your database objects and then Refresh. Expand the PC_DBT_DB database and you should see your development schema. Select the schema, then Tables and Views. Now you should be able to see

MY_FIRST_DBT_MODELas a table andMY_SECOND_DBT_MODELas a view.

Create branch and set up project configs

In this step, we’ll need to create a development branch and set up project level configurations.

-

To get started with development for our project, we'll need to create a new Git branch for our work. Select create branch and name your development branch. We'll call our branch

snowpark_python_workshopthen click Submit. -

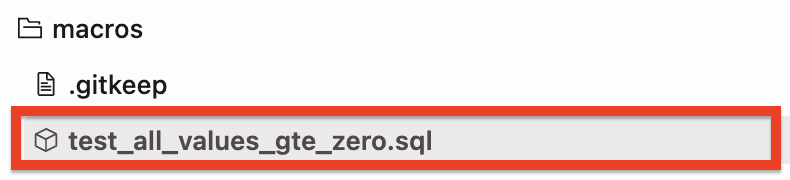

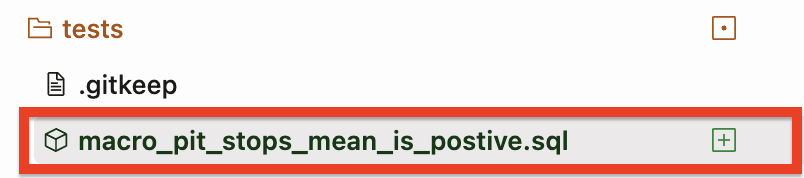

The first piece of development we'll do on the project is to update the

dbt_project.ymlfile. Every dbt project requires adbt_project.ymlfile — this is how dbt knows a directory is a dbt project. The dbt_project.yml file also contains important information that tells dbt how to operate on your project. -

Select the

dbt_project.ymlfile from the file tree to open it and replace all of the existing contents with the following code below. When you're done, save the file by clicking save. You can also use the Command-S or Control-S shortcut from here on out.# Name your project! Project names should contain only lowercase characters

# and underscores. A good package name should reflect your organization's

# name or the intended use of these models

name: 'snowflake_dbt_python_formula1'

version: '1.3.0'

require-dbt-version: '>=1.3.0'

config-version: 2

# This setting configures which "profile" dbt uses for this project.

profile: 'default'

# These configurations specify where dbt should look for different types of files.

# The `model-paths` config, for example, states that models in this project can be

# found in the "models/" directory. You probably won't need to change these!

model-paths: ["models"]

analysis-paths: ["analyses"]

test-paths: ["tests"]

seed-paths: ["seeds"]

macro-paths: ["macros"]

snapshot-paths: ["snapshots"]

target-path: "target" # directory which will store compiled SQL files

clean-targets: # directories to be removed by `dbt clean`

- "target"

- "dbt_packages"

models:

snowflake_dbt_python_formula1:

staging:

+docs:

node_color: "CadetBlue"

marts:

+materialized: table

aggregates:

+docs:

node_color: "Maroon"

+tags: "bi"

core:

+docs:

node_color: "#800080"

intermediate:

+docs:

node_color: "MediumSlateBlue"

ml:

prep:

+docs:

node_color: "Indigo"

train_predict:

+docs:

node_color: "#36454f" -

The key configurations to point out in the file with relation to the work that we're going to do are in the

modelssection.require-dbt-version— Tells dbt which version of dbt to use for your project. We are requiring 1.3.0 and any newer version to run python models and node colors.materialized— Tells dbt how to materialize models when compiling the code before it pushes it down to Snowflake. All models in themartsfolder will be built as tables.tags— Applies tags at a directory level to all models. All models in theaggregatesfolder will be tagged asbi(abbreviation for business intelligence).docs— Specifies thenode_coloreither by the plain color name or a hex value.

-

Materializations are strategies for persisting dbt models in a warehouse, with

tablesandviewsbeing the most commonly utilized types. By default, all dbt models are materialized as views and other materialization types can be configured in thedbt_project.ymlfile or in a model itself. It’s very important to note Python models can only be materialized as tables or incremental models. Since all our Python models exist undermarts, the following portion of ourdbt_project.ymlensures no errors will occur when we run our Python models. Starting with dbt version 1.4, Python files will automatically get materialized as tables even if not explicitly specified.marts:

+materialized: table

Create folders and organize files

dbt Labs has developed a project structure guide that contains a number of recommendations for how to build the folder structure for your project. Do check out that guide if you want to learn more. Right now we are going to create some folders to organize our files:

- Sources — This is our Formula 1 dataset and it will be defined in a source YAML file.

- Staging models — These models have a 1:1 with their source table.

- Intermediate — This is where we will be joining some Formula staging models.

- Marts models — Here is where we perform our major transformations. It contains these subfolders:

- aggregates

- core

- ml

-

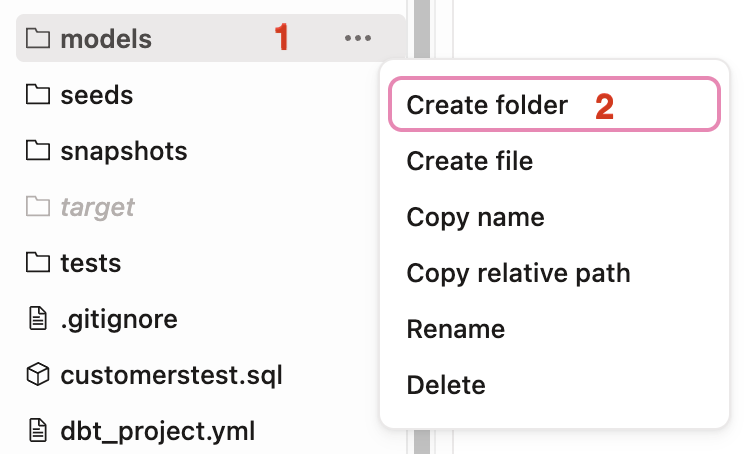

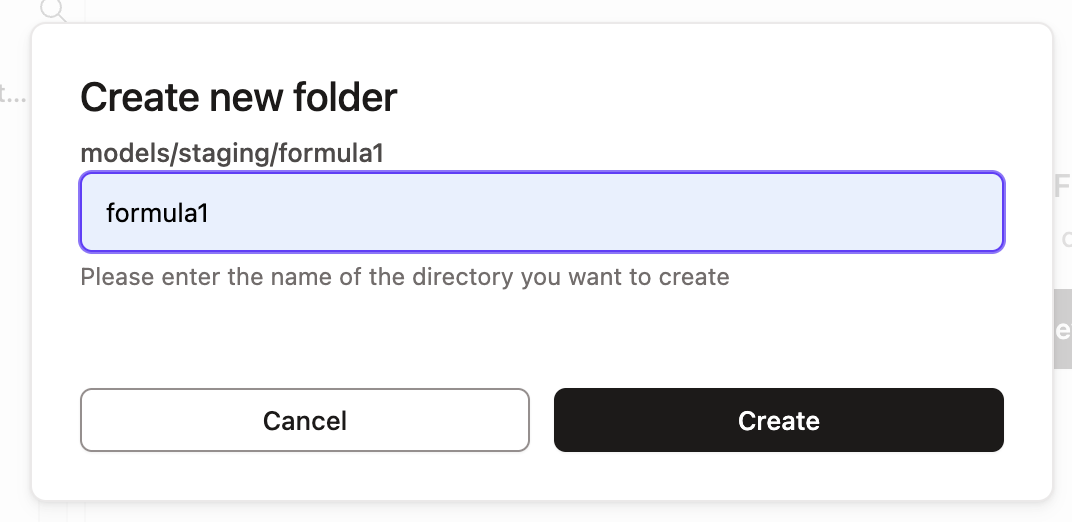

In your file tree, use your cursor and hover over the

modelssubdirectory, click the three dots … that appear to the right of the folder name, then select Create Folder. We're going to add two new folders to the file path,stagingandformula1(in that order) by typingstaging/formula1into the file path.- If you click into your

modelsdirectory now, you should see the newstagingfolder nested withinmodelsand theformula1folder nested withinstaging.

- If you click into your

-

Create two additional folders the same as the last step. Within the

modelssubdirectory, create new directoriesmarts/core. -

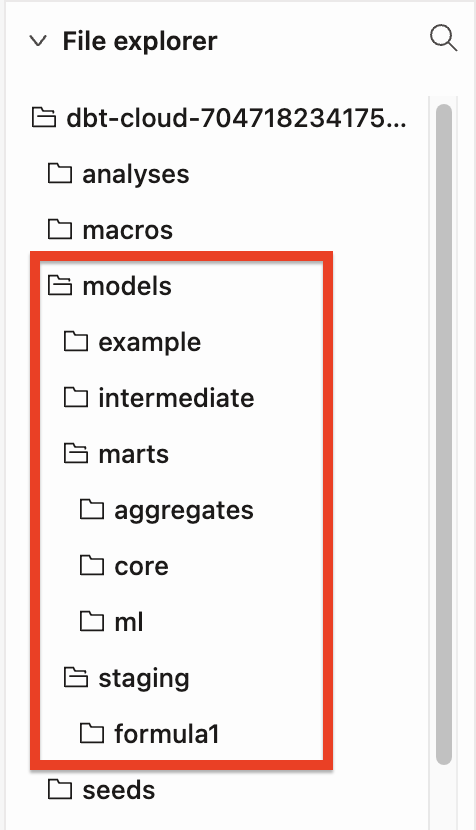

We will need to create a few more folders and subfolders using the UI. After you create all the necessary folders, your folder tree should look like this when it's all done:

Remember you can always reference the entire project in GitHub to view the complete folder and file strucutre.

Create source and staging models

In this section, we are going to create our source and staging models.

Sources allow us to create a dependency between our source database object and our staging models which will help us when we look at data lineage later. Also, if your source changes database or schema, you only have to update it in your f1_sources.yml file rather than updating all of the models it might be used in.

Staging models are the base of our project, where we bring all the individual components we're going to use to build our more complex and useful models into the project.

Since we want to focus on dbt and Python in this workshop, check out our sources and staging docs if you want to learn more (or take our dbt Fundamentals course which covers all of our core functionality).

1. Create sources

We're going to be using each of our 8 Formula 1 tables from our formula1 database under the raw schema for our transformations and we want to create those tables as sources in our project.

- Create a new file called

f1_sources.ymlwith the following file path:models/staging/formula1/f1_sources.yml. - Then, paste the following code into the file before saving it:

version: 2

sources:

- name: formula1

description: formula 1 datasets with normalized tables

database: formula1

schema: raw

tables:

- name: circuits

description: One record per circuit, which is the specific race course.

columns:

- name: circuitid

data_tests:

- unique

- not_null

- name: constructors

description: One record per constructor. Constructors are the teams that build their formula 1 cars.

columns:

- name: constructorid

data_tests:

- unique

- not_null

- name: drivers

description: One record per driver. This table gives details about the driver.

columns:

- name: driverid

data_tests:

- unique

- not_null

- name: lap_times

description: One row per lap in each race. Lap times started being recorded in this dataset in 1984 and joined through driver_id.

- name: pit_stops

description: One row per pit stop. Pit stops do not have their own id column, the combination of the race_id and driver_id identify the pit stop.

columns:

- name: stop

data_tests:

- accepted_values:

arguments: # available in v1.10.5 and higher. Older versions can set the <argument_name> as the top-level property.

values: [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

quote: false

- name: races

description: One race per row. Importantly this table contains the race year to understand trends.

columns:

- name: raceid

data_tests:

- unique

- not_null

- name: results

columns:

- name: resultid

data_tests:

- unique

- not_null

description: One row per result. The main table that we join out for grid and position variables.

- name: status

description: One status per row. The status contextualizes whether the race was finished or what issues arose e.g. collisions, engine, etc.

columns:

- name: statusid

data_tests:

- unique

- not_null

2. Create staging models

The next step is to set up the staging models for each of the 8 source tables. Given the one-to-one relationship between staging models and their corresponding source tables, we'll build 8 staging models here. We know it’s a lot and in the future, we will seek to update the workshop to make this step less repetitive and more efficient. This step is also a good representation of the real world of data, where you have multiple hierarchical tables that you will need to join together!

-

Let's go in alphabetical order to easily keep track of all our staging models! Create a new file called

stg_f1_circuits.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_circuits.sql. Then, paste the following code into the file before saving it:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','circuits') }}

),

renamed as (

select

circuitid as circuit_id,

circuitref as circuit_ref,

name as circuit_name,

location,

country,

lat as latitude,

lng as longitude,

alt as altitude

-- omit the url

from source

)

select * from renamedAll we're doing here is pulling the source data into the model using the

sourcefunction, renaming some columns, and omitting the columnurlwith a commented note since we don’t need it for our analysis. -

Create

stg_f1_constructors.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_constructors.sql. Paste the following code into it before saving the file:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','constructors') }}

),

renamed as (

select

constructorid as constructor_id,

constructorref as constructor_ref,

name as constructor_name,

nationality as constructor_nationality

-- omit the url

from source

)

select * from renamedWe have 6 other stages models to create. We can do this by creating new files, then copy and paste the code into our

stagingfolder. -

Create

stg_f1_drivers.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_drivers.sql:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','drivers') }}

),

renamed as (

select

driverid as driver_id,

driverref as driver_ref,

number as driver_number,

code as driver_code,

forename,

surname,

dob as date_of_birth,

nationality as driver_nationality

-- omit the url

from source

)

select * from renamed -

Create

stg_f1_lap_times.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_lap_times.sql:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','lap_times') }}

),

renamed as (

select

raceid as race_id,

driverid as driver_id,

lap,

position,

time as lap_time_formatted,

milliseconds as lap_time_milliseconds

from source

)

select * from renamed -

Create

stg_f1_pit_stops.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_pit_stops.sql:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','pit_stops') }}

),

renamed as (

select

raceid as race_id,

driverid as driver_id,

stop as stop_number,

lap,

time as lap_time_formatted,

duration as pit_stop_duration_seconds,

milliseconds as pit_stop_milliseconds

from source

)

select * from renamed

order by pit_stop_duration_seconds desc -

Create

stg_f1_races.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_races.sql:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','races') }}

),

renamed as (

select

raceid as race_id,

year as race_year,

round as race_round,

circuitid as circuit_id,

name as circuit_name,

date as race_date,

to_time(time) as race_time,

-- omit the url

fp1_date as free_practice_1_date,

fp1_time as free_practice_1_time,

fp2_date as free_practice_2_date,

fp2_time as free_practice_2_time,

fp3_date as free_practice_3_date,

fp3_time as free_practice_3_time,

quali_date as qualifying_date,

quali_time as qualifying_time,

sprint_date,

sprint_time

from source

)

select * from renamed -

Create

stg_f1_results.sqlwith this file pathmodels/staging/formula1/stg_f1_results.sql:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','results') }}

),

renamed as (

select

resultid as result_id,

raceid as race_id,

driverid as driver_id,

constructorid as constructor_id,

number as driver_number,

grid,

position::int as position,

positiontext as position_text,

positionorder as position_order,

points,

laps,

time as results_time_formatted,

milliseconds as results_milliseconds,

fastestlap as fastest_lap,

rank as results_rank,

fastestlaptime as fastest_lap_time_formatted,

fastestlapspeed::decimal(6,3) as fastest_lap_speed,

statusid as status_id

from source

)

select * from renamed -

Last one! Create

stg_f1_status.sqlwith this file path:models/staging/formula1/stg_f1_status.sql:with

source as (

select * from {{ source('formula1','status') }}

),

renamed as (

select

statusid as status_id,

status

from source

)

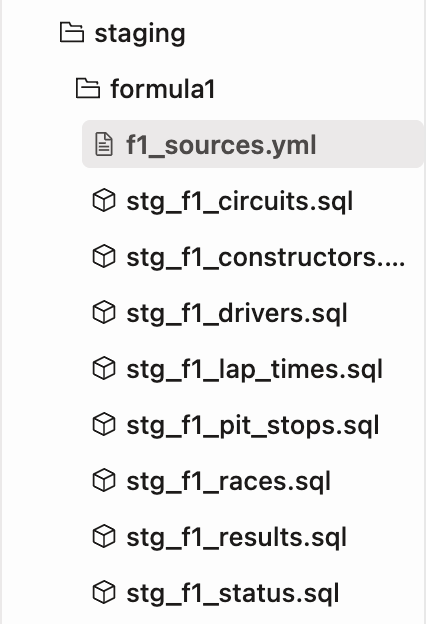

select * from renamedAfter the source and all the staging models are complete for each of the 8 tables, your staging folder should look like this:

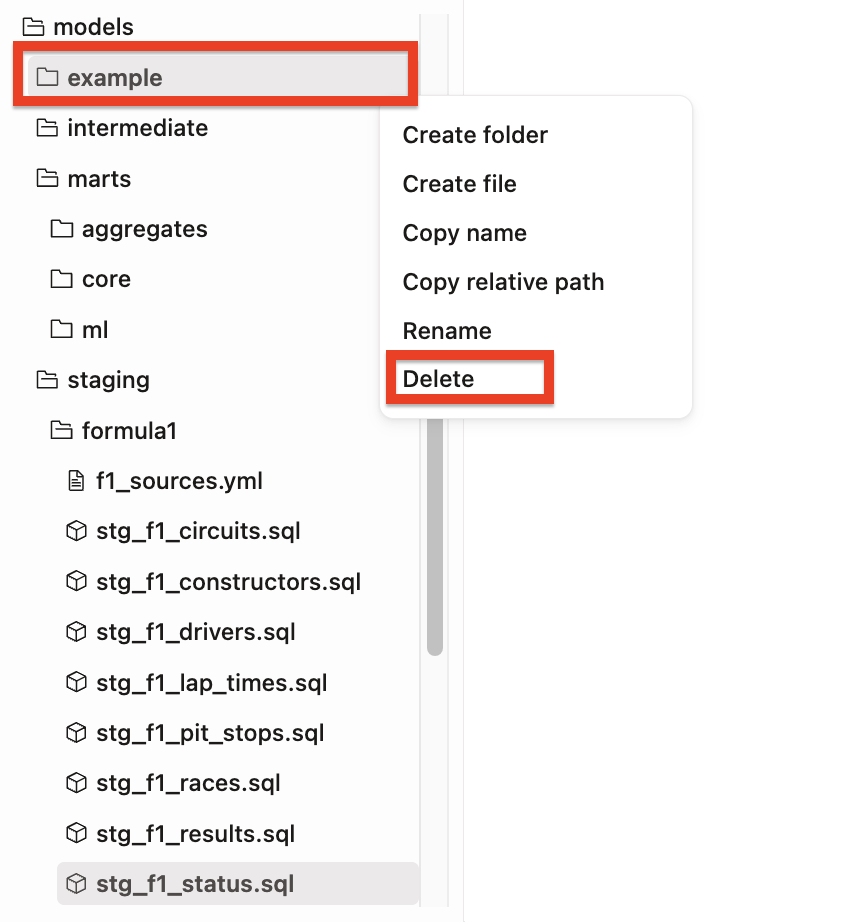

-

It’s a good time to delete our example folder since these two models are extraneous to our formula1 pipeline and

my_first_modelfails anot_nulltest that we won’t spend time investigating. dbt will warn us that this folder will be permanently deleted, and we are okay with that so select Delete. -

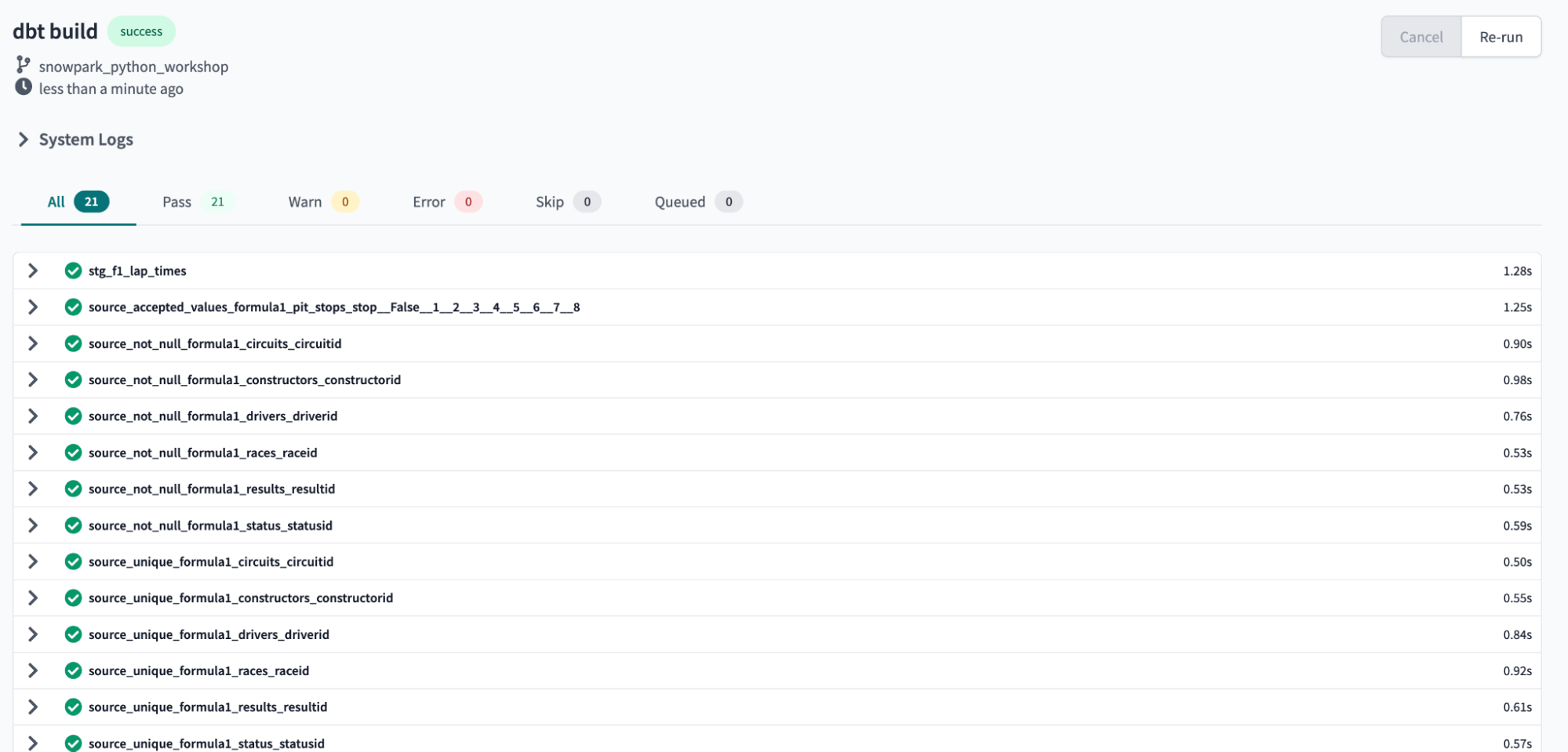

Now that the staging models are built and saved, it's time to create the models in our development schema in Snowflake. To do this we're going to enter into the command line

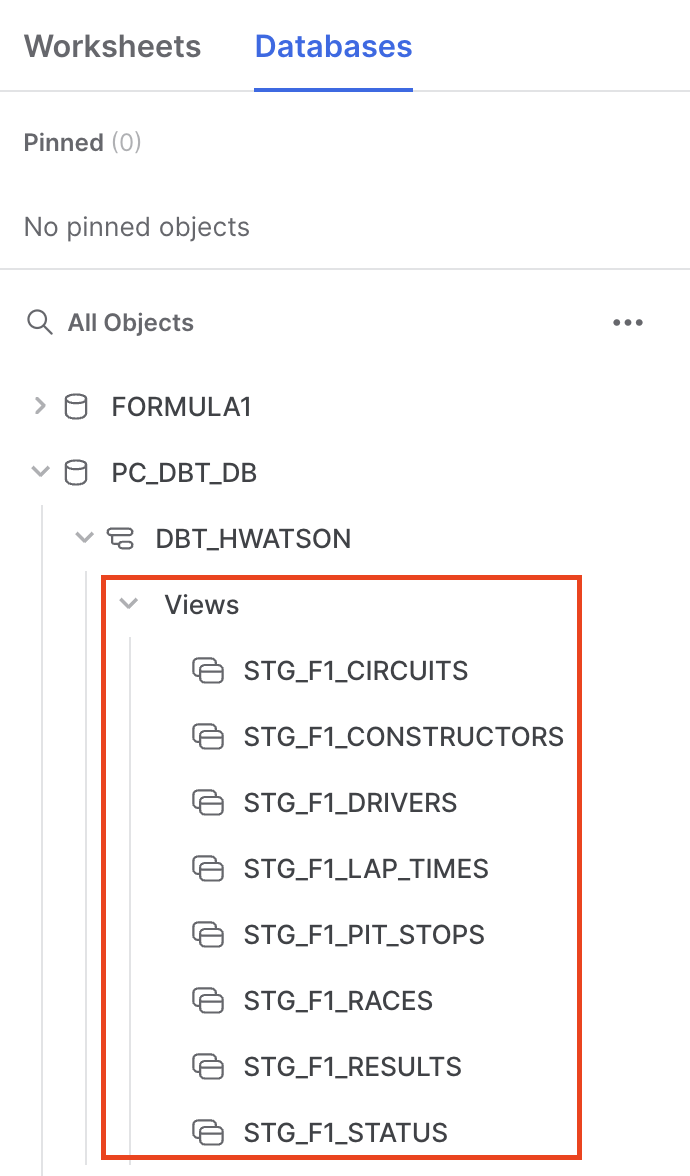

dbt buildto run all of the models in our project, which includes the 8 new staging models and the existing example models.Your run should complete successfully and you should see green checkmarks next to all of your models in the run results. We built our 8 staging models as views and ran 13 source tests that we configured in the

f1_sources.ymlfile with not that much code, pretty cool!Let's take a quick look in Snowflake, refresh database objects, open our development schema, and confirm that the new models are there. If you can see them, then we're good to go!

Before we move onto the next section, be sure to commit your new models to your Git branch. Click Commit and push and give your commit a message like

profile, sources, and staging setupbefore moving on.

Transform SQL

Now that we have all our sources and staging models done, it's time to move into where dbt shines — transformation!

We need to:

- Create some intermediate tables to join tables that aren’t hierarchical

- Create core tables for business intelligence (BI) tool ingestion

- Answer the two questions about:

- fastest pit stops

- lap time trends about our Formula 1 data by creating aggregate models using python!

Intermediate models

We need to join lots of reference tables to our results table to create a human readable dataframe. What does this mean? For example, we don’t only want to have the numeric status_id in our table, we want to be able to read in a row of data that a driver could not finish a race due to engine failure (status_id=5).

By now, we are pretty good at creating new files in the correct directories so we won’t cover this in detail. All intermediate models should be created in the path models/intermediate.

-

Create a new file called

int_lap_times_years.sql. In this model, we are joining our lap time and race information so we can look at lap times over years. In earlier Formula 1 eras, lap times were not recorded (only final results), so we filter out records where lap times are null.with lap_times as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_lap_times') }}

),

races as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_races') }}

),

expanded_lap_times_by_year as (

select

lap_times.race_id,

driver_id,

race_year,

lap,

lap_time_milliseconds

from lap_times

left join races

on lap_times.race_id = races.race_id

where lap_time_milliseconds is not null

)

select * from expanded_lap_times_by_year -

Create a file called

in_pit_stops.sql. Pit stops are a many-to-one (M:1) relationship with our races. We are creating a feature calledtotal_pit_stops_per_raceby partitioning over ourrace_idanddriver_id, while preserving individual level pit stops for rolling average in our next section.with stg_f1__pit_stops as

(

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_pit_stops') }}

),

pit_stops_per_race as (

select

race_id,

driver_id,

stop_number,

lap,

lap_time_formatted,

pit_stop_duration_seconds,

pit_stop_milliseconds,

max(stop_number) over (partition by race_id,driver_id) as total_pit_stops_per_race

from stg_f1__pit_stops

)

select * from pit_stops_per_race -

Create a file called

int_results.sql. Here we are using 4 of our tables —races,drivers,constructors, andstatus— to give context to ourresultstable. We are now able to calculate a new featuredrivers_age_yearsby bringing thedate_of_birthandrace_yearinto the same table. We are also creating a column to indicate if the driver did not finish (dnf) the race, based upon if theirpositionwas null called,dnf_flag.with results as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_results') }}

),

races as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_races') }}

),

drivers as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_drivers') }}

),

constructors as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_constructors') }}

),

status as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_status') }}

),

int_results as (

select

result_id,

results.race_id,

race_year,

race_round,

circuit_id,

circuit_name,

race_date,

race_time,

results.driver_id,

results.driver_number,

forename ||' '|| surname as driver,

cast(datediff('year', date_of_birth, race_date) as int) as drivers_age_years,

driver_nationality,

results.constructor_id,

constructor_name,

constructor_nationality,

grid,

position,

position_text,

position_order,

points,

laps,

results_time_formatted,

results_milliseconds,

fastest_lap,

results_rank,

fastest_lap_time_formatted,

fastest_lap_speed,

results.status_id,

status,

case when position is null then 1 else 0 end as dnf_flag

from results

left join races

on results.race_id=races.race_id

left join drivers

on results.driver_id = drivers.driver_id

left join constructors

on results.constructor_id = constructors.constructor_id

left join status

on results.status_id = status.status_id

)

select * from int_results -

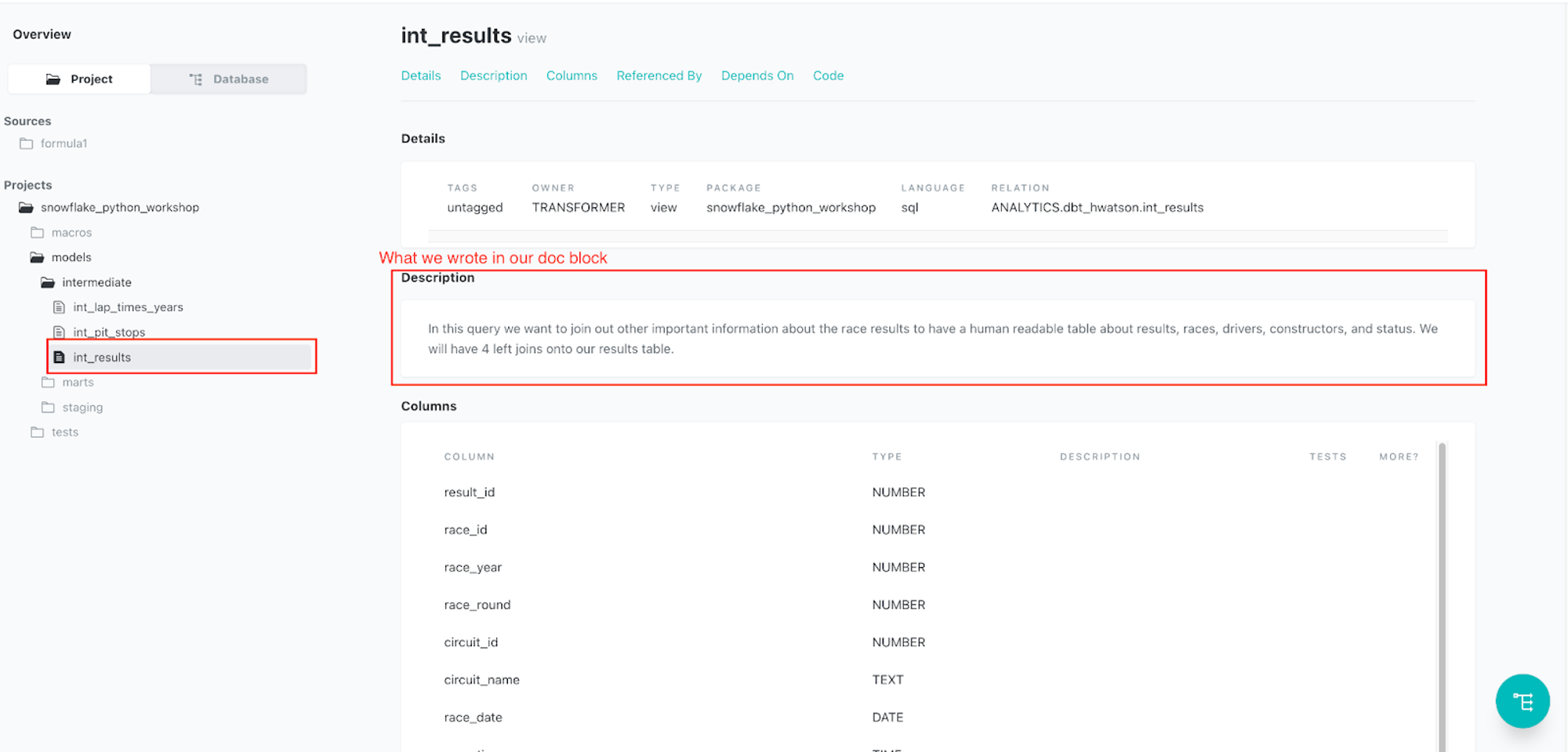

Create a Markdown file

intermediate.mdthat we will go over in depth in the Test and Documentation sections of the Leverage dbt to generate analytics and ML-ready pipelines with SQL and Python with Snowflake guide.# the intent of this .md is to allow for multi-line long form explanations for our intermediate transformations

# below are descriptions

{% docs int_results %} In this query we want to join out other important information about the race results to have a human readable table about results, races, drivers, constructors, and status.

We will have 4 left joins onto our results table. {% enddocs %}

{% docs int_pit_stops %} There are many pit stops within one race, aka a M:1 relationship.

We want to aggregate this so we can properly join pit stop information without creating a fanout. {% enddocs %}

{% docs int_lap_times_years %} Lap times are done per lap. We need to join them out to the race year to understand yearly lap time trends. {% enddocs %} -

Create a YAML file

intermediate.ymlthat we will go over in depth during the Test and Document sections of the Leverage dbt to generate analytics and ML-ready pipelines with SQL and Python with Snowflake guide.version: 2

models:

- name: int_results

description: '{{ doc("int_results") }}'

- name: int_pit_stops

description: '{{ doc("int_pit_stops") }}'

- name: int_lap_times_years

description: '{{ doc("int_lap_times_years") }}'That wraps up the intermediate models we need to create our core models!

Core models

-

Create a file

fct_results.sql. This is what I like to refer to as the “mega table” — a really large denormalized table with all our context added in at row level for human readability. Importantly, we have a tablecircuitsthat is linked through the tableraces. When we joinedracestoresultsinint_results.sqlwe allowed our tables to make the connection fromcircuitstoresultsinfct_results.sql. We are only taking information about pit stops at the result level so our join would not cause a fanout.with int_results as (

select * from {{ ref('int_results') }}

),

int_pit_stops as (

select

race_id,

driver_id,

max(total_pit_stops_per_race) as total_pit_stops_per_race

from {{ ref('int_pit_stops') }}

group by 1,2

),

circuits as (

select * from {{ ref('stg_f1_circuits') }}

),

base_results as (

select

result_id,

int_results.race_id,

race_year,

race_round,

int_results.circuit_id,

int_results.circuit_name,

circuit_ref,

location,

country,

latitude,

longitude,

altitude,

total_pit_stops_per_race,

race_date,

race_time,

int_results.driver_id,

driver,

driver_number,

drivers_age_years,

driver_nationality,

constructor_id,

constructor_name,

constructor_nationality,

grid,

position,

position_text,

position_order,

points,

laps,

results_time_formatted,

results_milliseconds,

fastest_lap,

results_rank,

fastest_lap_time_formatted,

fastest_lap_speed,

status_id,

status,

dnf_flag

from int_results

left join circuits

on int_results.circuit_id=circuits.circuit_id

left join int_pit_stops

on int_results.driver_id=int_pit_stops.driver_id and int_results.race_id=int_pit_stops.race_id

)

select * from base_results -

Create the file

pit_stops_joined.sql. Our results and pit stops are at different levels of dimensionality (also called grain). Simply put, we have multiple pit stops per a result. Since we are interested in understanding information at the pit stop level with information about race year and constructor, we will create a new tablepit_stops_joined.sqlwhere each row is per pit stop. Our new table tees up our aggregation in Python.with base_results as (

select * from {{ ref('fct_results') }}

),

pit_stops as (

select * from {{ ref('int_pit_stops') }}

),

pit_stops_joined as (

select

base_results.race_id,

race_year,

base_results.driver_id,

constructor_id,

constructor_name,

stop_number,

lap,

lap_time_formatted,

pit_stop_duration_seconds,

pit_stop_milliseconds

from base_results

left join pit_stops

on base_results.race_id=pit_stops.race_id and base_results.driver_id=pit_stops.driver_id

)

select * from pit_stops_joined -

Enter in the command line and execute

dbt buildto build out our entire pipeline to up to this point. Don’t worry about “overriding” your previous models – dbt workflows are designed to be idempotent so we can run them again and expect the same results. -

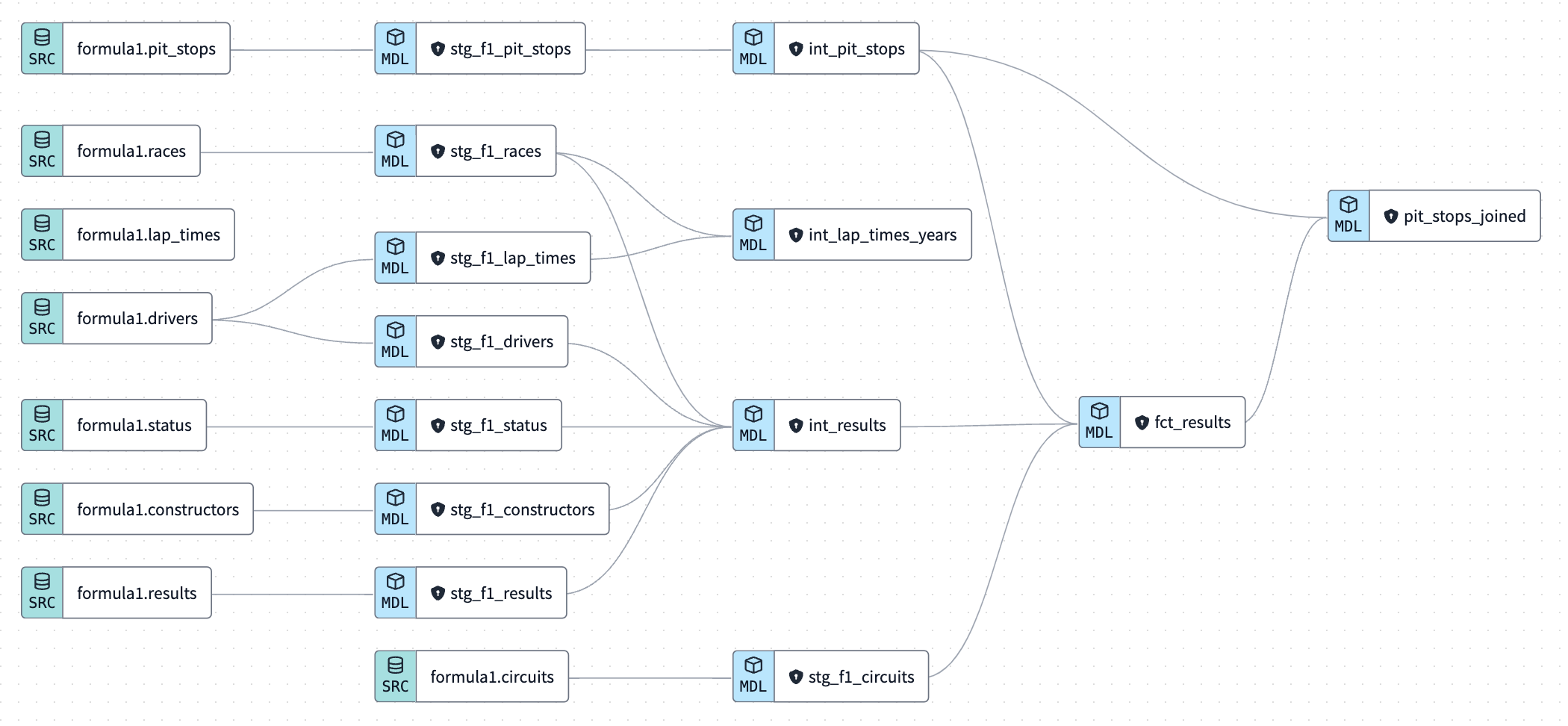

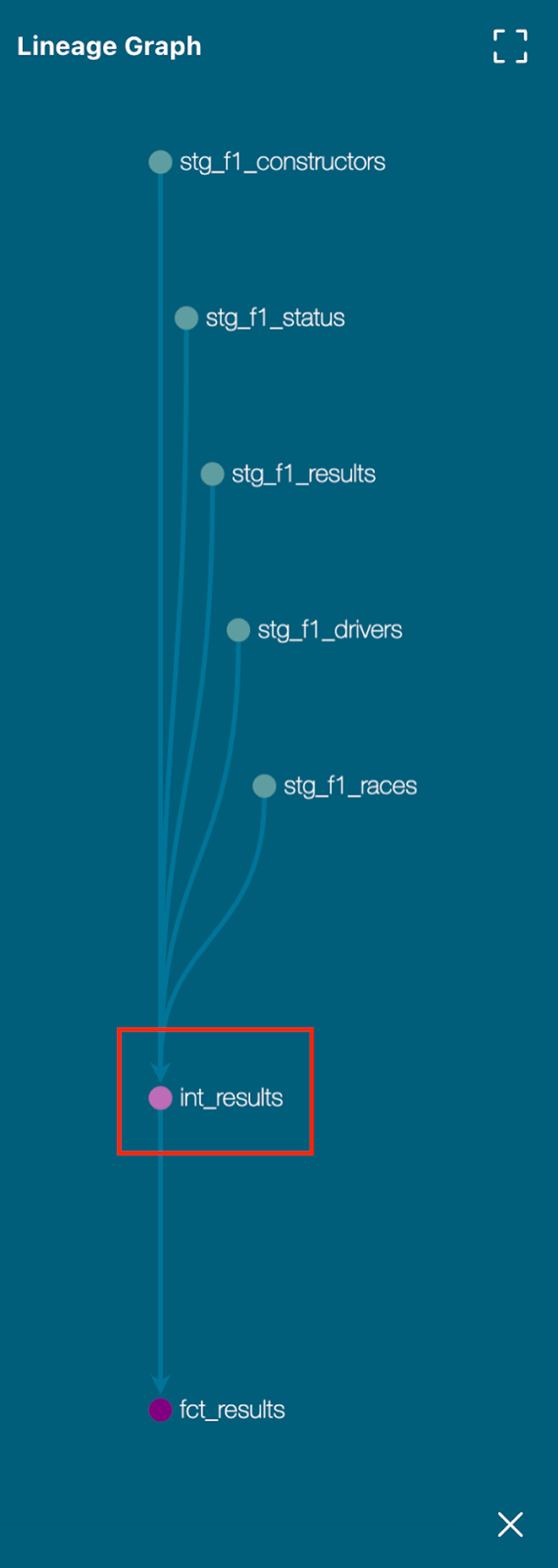

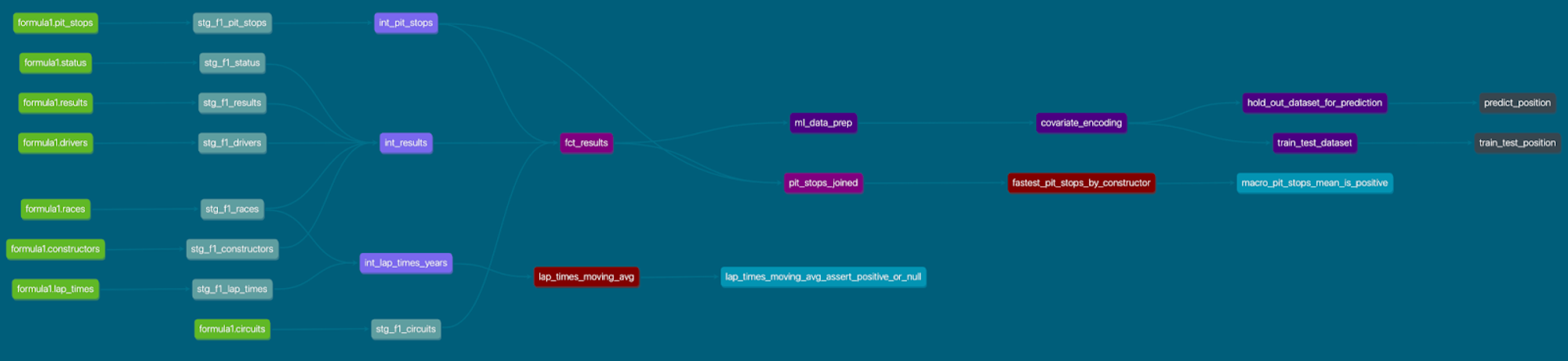

Let’s talk about our lineage so far. It’s looking good 😎. We’ve shown how SQL can be used to make data type, column name changes, and handle hierarchical joins really well; all while building out our automated lineage!

-

Time to Commit and push our changes and give your commit a message like

intermediate and fact modelsbefore moving on.

Running dbt Python models

Up until now, SQL has been driving the project (car pun intended) for data cleaning and hierarchical joining. Now it’s time for Python to take the wheel (car pun still intended) for the rest of our lab! For more information about running Python models on dbt, check out our docs. To learn more about dbt python works under the hood, check out Snowpark for Python, which makes running dbt Python models possible.

There are quite a few differences between SQL and Python in terms of the dbt syntax and DDL, so we’ll be breaking our code and model runs down further for our python models.

Pit stop analysis

First, we want to find out: which constructor had the fastest pit stops in 2021? (constructor is a Formula 1 team that builds or “constructs” the car).

-

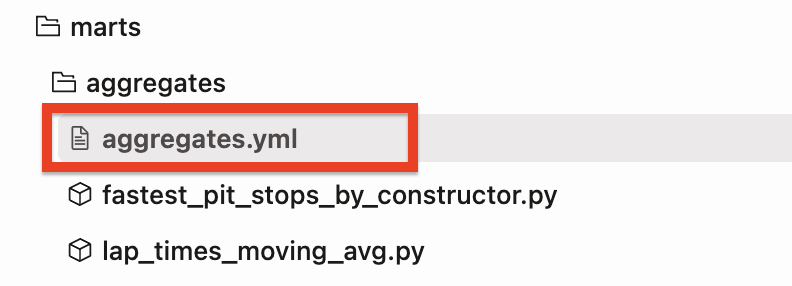

Create a new file called

fastest_pit_stops_by_constructor.pyin ouraggregates(this is the first time we are using the.pyextension!). -

Copy the following code into the file:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

def model(dbt, session):

# dbt configuration

dbt.config(packages=["pandas","numpy"])

# get upstream data

pit_stops_joined = dbt.ref("pit_stops_joined").to_pandas()

# provide year so we do not hardcode dates

year=2021

# describe the data

pit_stops_joined["PIT_STOP_SECONDS"] = pit_stops_joined["PIT_STOP_MILLISECONDS"]/1000

fastest_pit_stops = pit_stops_joined[(pit_stops_joined["RACE_YEAR"]==year)].groupby(by="CONSTRUCTOR_NAME")["PIT_STOP_SECONDS"].describe().sort_values(by='mean')

fastest_pit_stops.reset_index(inplace=True)

fastest_pit_stops.columns = fastest_pit_stops.columns.str.upper()

return fastest_pit_stops.round(2) -

Let’s break down what this code is doing step by step:

- First, we are importing the Python libraries that we are using. A library is a reusable chunk of code that someone else wrote that you may want to include in your programs/projects. We are using

numpyandpandasin this Python model. This is similar to a dbt package, but our Python libraries do not persist across the entire project. - Defining a function called

modelwith the parameterdbtandsession. The parameterdbtis a class compiled by dbt, which enables you to run your Python code in the context of your dbt project and DAG. The parametersessionis a class representing your Snowflake’s connection to the Python backend. Themodelfunction must return a single DataFrame. You can see that all the data transformation happening is within the body of themodelfunction that thereturnstatement is tied to. - Then, within the context of our dbt model library, we are passing in a configuration of which packages we need using

dbt.config(packages=["pandas","numpy"]). - Use the

.ref()function to retrieve the data framepit_stops_joinedthat we created in our last step using SQL. We cast this to a pandas dataframe (by default it's a Snowpark Dataframe). - Create a variable named

yearso we aren’t passing a hardcoded value. - Generate a new column called

PIT_STOP_SECONDSby dividing the value ofPIT_STOP_MILLISECONDSby 1000. - Create our final data frame

fastest_pit_stopsthat holds the records where year is equal to our year variable (2021 in this case), then group the data frame byCONSTRUCTOR_NAMEand use thedescribe()andsort_values()and in descending order. This will make our first row in the new aggregated data frame the team with the fastest pit stops over an entire competition year. - Finally, it resets the index of the

fastest_pit_stopsdata frame. Thereset_index()method allows you to reset the index back to the default 0, 1, 2, etc indexes. By default, this method will keep the "old" indexes in a column named "index"; to avoid this, use the drop parameter. Think of this as keeping your data “flat and square” as opposed to “tiered”. If you are new to Python, now might be a good time to learn about indexes for 5 minutes since it's the foundation of how Python retrieves, slices, and dices data. Theinplaceargument means we override the existing data frame permanently. Not to fear! This is what we want to do to avoid dealing with multi-indexed dataframes! - Convert our Python column names to all uppercase using

.upper(), so Snowflake recognizes them. - Finally we are returning our dataframe with 2 decimal places for all the columns using the

round()method.

- First, we are importing the Python libraries that we are using. A library is a reusable chunk of code that someone else wrote that you may want to include in your programs/projects. We are using

-

Zooming out a bit, what are we doing differently here in Python from our typical SQL code:

- Method chaining is a technique in which multiple methods are called on an object in a single statement, with each method call modifying the result of the previous one. The methods are called in a chain, with the output of one method being used as the input for the next one. The technique is used to simplify the code and make it more readable by eliminating the need for intermediate variables to store the intermediate results.

- The way you see method chaining in Python is the syntax

.().(). For example,.describe().sort_values(by='mean')where the.describe()method is chained to.sort_values().

- The way you see method chaining in Python is the syntax

- The

.describe()method is used to generate various summary statistics of the dataset. It's used on pandas dataframe. It gives a quick and easy way to get the summary statistics of your dataset without writing multiple lines of code. - The

.sort_values()method is used to sort a pandas dataframe or a series by one or multiple columns. The method sorts the data by the specified column(s) in ascending or descending order. It is the pandas equivalent toorder byin SQL.

We won’t go as in depth for our subsequent scripts, but will continue to explain at a high level what new libraries, functions, and methods are doing.

- Method chaining is a technique in which multiple methods are called on an object in a single statement, with each method call modifying the result of the previous one. The methods are called in a chain, with the output of one method being used as the input for the next one. The technique is used to simplify the code and make it more readable by eliminating the need for intermediate variables to store the intermediate results.

-

Build the model using the UI which will execute:

dbt run --select fastest_pit_stops_by_constructorin the command bar.

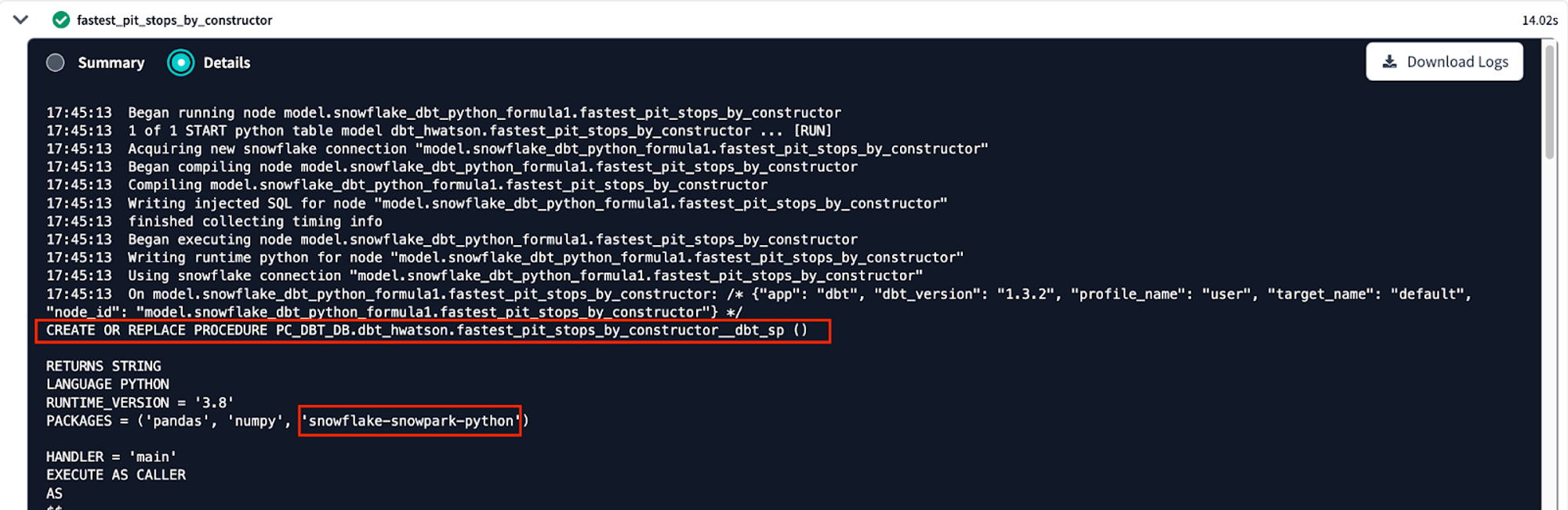

Let’s look at some details of our first Python model to see what our model executed. There two major differences we can see while running a Python model compared to an SQL model:

- Our Python model was executed as a stored procedure. Snowflake needs a way to know that it's meant to execute this code in a Python runtime, instead of interpreting in a SQL runtime. We do this by creating a Python stored proc, called by a SQL command.

- The

snowflake-snowpark-pythonlibrary has been picked up to execute our Python code. Even though this wasn’t explicitly stated this is picked up by the dbt class object because we need our Snowpark package to run Python!

Python models take a bit longer to run than SQL models, however we could always speed this up by using Snowpark-optimized Warehouses if we wanted to. Our data is sufficiently small, so we won’t worry about creating a separate warehouse for Python versus SQL files today.

The rest of our Details output gives us information about how dbt and Snowpark for Python are working together to define class objects and apply a specific set of methods to run our models.

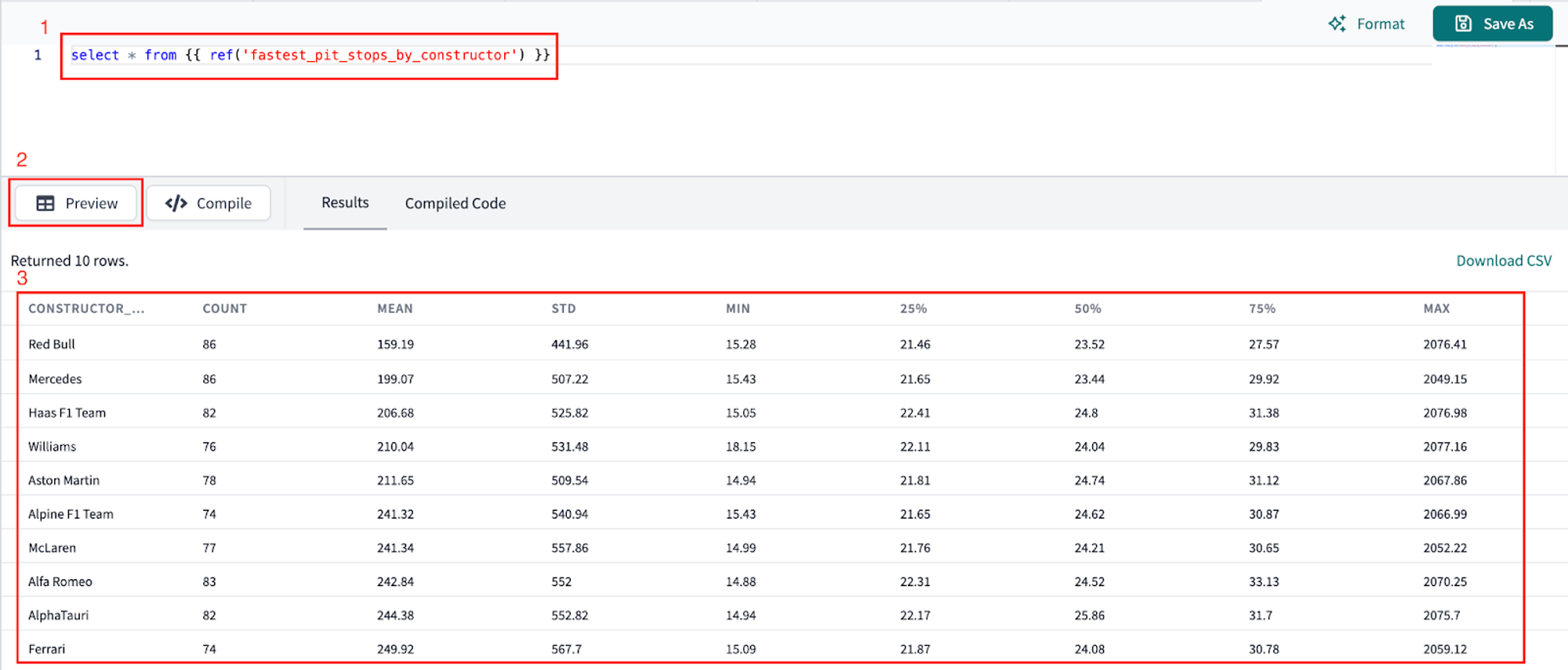

So which constructor had the fastest pit stops in 2021? Let’s look at our data to find out!

-

We can't preview Python models directly, so let’s create a new file using the + button or the Control-n shortcut to create a new scratchpad.

-

Reference our Python model:

select * from {{ ref('fastest_pit_stops_by_constructor') }}and preview the output:

Not only did Red Bull have the fastest average pit stops by nearly 40 seconds, they also had the smallest standard deviation, meaning they are both fastest and most consistent teams in pit stops. By using the

.describe()method we were able to avoid verbose SQL requiring us to create a line of code per column and repetitively use thePERCENTILE_COUNT()function.Now we want to find the lap time average and rolling average through the years (is it generally trending up or down)?

-

Create a new file called

lap_times_moving_avg.pyin ouraggregatesfolder. -

Copy the following code into the file:

import pandas as pd

def model(dbt, session):

# dbt configuration

dbt.config(packages=["pandas"])

# get upstream data

lap_times = dbt.ref("int_lap_times_years").to_pandas()

# describe the data

lap_times["LAP_TIME_SECONDS"] = lap_times["LAP_TIME_MILLISECONDS"]/1000

lap_time_trends = lap_times.groupby(by="RACE_YEAR")["LAP_TIME_SECONDS"].mean().to_frame()

lap_time_trends.reset_index(inplace=True)

lap_time_trends["LAP_MOVING_AVG_5_YEARS"] = lap_time_trends["LAP_TIME_SECONDS"].rolling(5).mean()

lap_time_trends.columns = lap_time_trends.columns.str.upper()

return lap_time_trends.round(1) -

Breaking down our code a bit:

- We’re only using the

pandaslibrary for this model and casting it to a pandas data frame.to_pandas(). - Generate a new column called

LAP_TIMES_SECONDSby dividing the value ofLAP_TIME_MILLISECONDSby 1000. - Create the final dataframe. Get the lap time per year. Calculate the mean series and convert to a data frame.

- Reset the index.

- Calculate the rolling 5 year mean.

- Round our numeric columns to one decimal place.

- We’re only using the

-

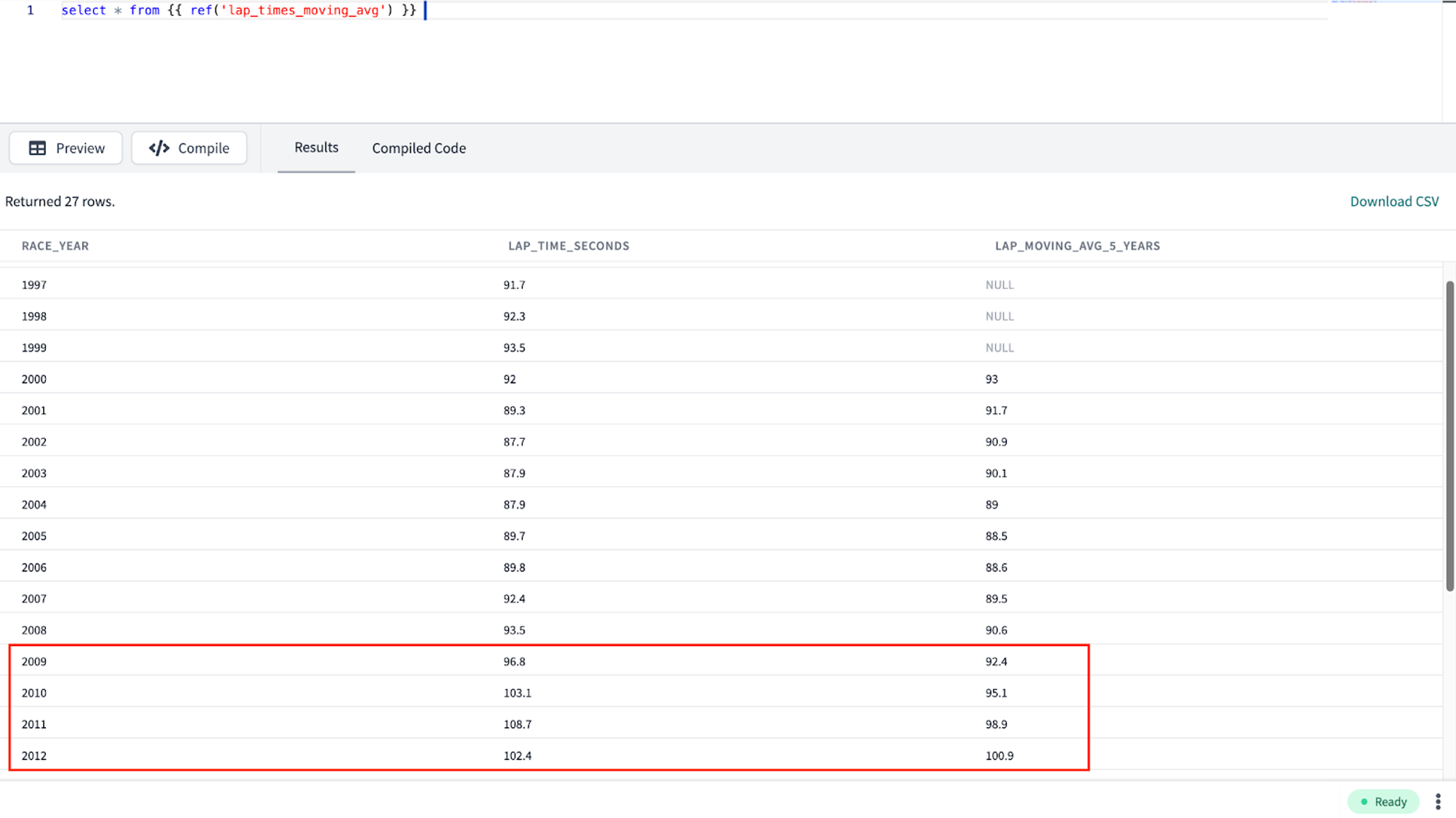

Now, run this model by using the UI Run model or

dbt run --select lap_times_moving_avg

in the command bar.

-

Once again previewing the output of our data using the same steps for our

fastest_pit_stops_by_constructormodel.We can see that it looks like lap times are getting consistently faster over time. Then in 2010 we see an increase occur! Using outside subject matter context, we know that significant rule changes were introduced to Formula 1 in 2010 and 2011 causing slower lap times.

-

Now is a good time to checkpoint and commit our work to Git. Click Commit and push and give your commit a message like

aggregate python modelsbefore moving on.

The dbt model, .source(), .ref() and .config() functions

Let’s take a step back before starting machine learning to both review and go more in-depth at the methods that make running dbt python models possible. If you want to know more outside of this lab’s explanation read the documentation here.

- dbt model(dbt, session). For starters, each Python model lives in a .py file in your models/ folder. It defines a function named

model(), which takes two parameters:- dbt — A class compiled by dbt Core, unique to each model, enables you to run your Python code in the context of your dbt project and DAG.

- session — A class representing your data platform’s connection to the Python backend. The session is needed to read in tables as DataFrames and to write DataFrames back to tables. In PySpark, by convention, the SparkSession is named spark, and available globally. For consistency across platforms, we always pass it into the model function as an explicit argument called session.

- The

model()function must return a single DataFrame. On Snowpark (Snowflake), this can be a Snowpark or pandas DataFrame. .source()and.ref()functions. Python models participate fully in dbt's directed acyclic graph (DAG) of transformations. If you want to read directly from a raw source table, usedbt.source(). We saw this in our earlier section using SQL with the source function. These functions have the same execution, but with different syntax. Use thedbt.ref()method within a Python model to read data from other models (SQL or Python). These methods return DataFrames pointing to the upstream source, model, seed, or snapshot..config(). Just like SQL models, there are three ways to configure Python models:-

In a dedicated

.ymlfile, within themodels/directory -

Within the model's

.pyfile, using thedbt.config()method -

Calling the

dbt.config()method will set configurations for your model within your.pyfile, similar to the{{ config() }} macroin.sqlmodel files:def model(dbt, session):

# setting configuration

dbt.config(materialized="table") -

There's a limit to how complex you can get with the

dbt.config()method. It accepts only literal values (strings, booleans, and numeric types). Passing another function or a more complex data structure is not possible. The reason is that dbt statically analyzes the arguments to.config()while parsing your model without executing your Python code. If you need to set a more complex configuration, we recommend you define it using the config property in a YAML file. Learn more about configurations here.

-

Prepare for machine learning: cleaning, encoding, and splits

Now that we’ve gained insights and business intelligence about Formula 1 at a descriptive level, we want to extend our capabilities into prediction. We’re going to take the scenario where we censor the data. This means that we will pretend that we will train a model using earlier data and apply it to future data. In practice, this means we’ll take data from 2010-2019 to train our model and then predict 2020 data.

In this section, we’ll be preparing our data to predict the final race position of a driver.

At a high level we’ll be:

- Creating new prediction features and filtering our dataset to active drivers

- Encoding our data (algorithms like numbers) and simplifying our target variable called

position - Splitting our dataset into training, testing, and validation

ML data prep

-

To keep our project organized, we’ll need to create two new subfolders in our

mldirectory. Under themlfolder, make the subfoldersprepandtrain_predict. -

Create a new file under

ml/prepcalledml_data_prep.py. Copy the following code into the file and Save.import pandas as pd

def model(dbt, session):

# dbt configuration

dbt.config(packages=["pandas"])

# get upstream data

fct_results = dbt.ref("fct_results").to_pandas()

# provide years so we do not hardcode dates in filter command

start_year=2010

end_year=2020

# describe the data for a full decade

data = fct_results.loc[fct_results['RACE_YEAR'].between(start_year, end_year)]

# convert string to an integer

data['POSITION'] = data['POSITION'].astype(float)

# we cannot have nulls if we want to use total pit stops

data['TOTAL_PIT_STOPS_PER_RACE'] = data['TOTAL_PIT_STOPS_PER_RACE'].fillna(0)

# some of the constructors changed their name over the year so replacing old names with current name

mapping = {'Force India': 'Racing Point', 'Sauber': 'Alfa Romeo', 'Lotus F1': 'Renault', 'Toro Rosso': 'AlphaTauri'}

data['CONSTRUCTOR_NAME'].replace(mapping, inplace=True)

# create confidence metrics for drivers and constructors

dnf_by_driver = data.groupby('DRIVER').sum(numeric_only=True)['DNF_FLAG']

driver_race_entered = data.groupby('DRIVER').count()['DNF_FLAG']

driver_dnf_ratio = (dnf_by_driver/driver_race_entered)

driver_confidence = 1-driver_dnf_ratio

driver_confidence_dict = dict(zip(driver_confidence.index,driver_confidence))

dnf_by_constructor = data.groupby('CONSTRUCTOR_NAME').sum(numeric_only=True)['DNF_FLAG']

constructor_race_entered = data.groupby('CONSTRUCTOR_NAME').count()['DNF_FLAG']

constructor_dnf_ratio = (dnf_by_constructor/constructor_race_entered)

constructor_relaiblity = 1-constructor_dnf_ratio

constructor_relaiblity_dict = dict(zip(constructor_relaiblity.index,constructor_relaiblity))

data['DRIVER_CONFIDENCE'] = data['DRIVER'].apply(lambda x:driver_confidence_dict[x])

data['CONSTRUCTOR_RELAIBLITY'] = data['CONSTRUCTOR_NAME'].apply(lambda x:constructor_relaiblity_dict[x])

#removing retired drivers and constructors

active_constructors = ['Renault', 'Williams', 'McLaren', 'Ferrari', 'Mercedes',

'AlphaTauri', 'Racing Point', 'Alfa Romeo', 'Red Bull',

'Haas F1 Team']

active_drivers = ['Daniel Ricciardo', 'Kevin Magnussen', 'Carlos Sainz',

'Valtteri Bottas', 'Lance Stroll', 'George Russell',

'Lando Norris', 'Sebastian Vettel', 'Kimi Räikkönen',

'Charles Leclerc', 'Lewis Hamilton', 'Daniil Kvyat',

'Max Verstappen', 'Pierre Gasly', 'Alexander Albon',

'Sergio Pérez', 'Esteban Ocon', 'Antonio Giovinazzi',

'Romain Grosjean','Nicholas Latifi']

# create flags for active drivers and constructors so we can filter downstream

data['ACTIVE_DRIVER'] = data['DRIVER'].apply(lambda x: int(x in active_drivers))

data['ACTIVE_CONSTRUCTOR'] = data['CONSTRUCTOR_NAME'].apply(lambda x: int(x in active_constructors))

return data -

As usual, let’s break down what we are doing in this Python model:

- We’re first referencing our upstream

fct_resultstable and casting it to a pandas dataframe. - Filtering on years 2010-2020 since we’ll need to clean all our data we are using for prediction (both training and testing).

- Filling in empty data for

total_pit_stopsand making a mapping active constructors and drivers to avoid erroneous predictions- ⚠️ You might be wondering why we didn’t do this upstream in our

fct_resultstable! The reason for this is that we want our machine learning cleanup to reflect the year 2020 for our predictions and give us an up-to-date team name. However, for business intelligence purposes we can keep the historical data at that point in time. Instead of thinking of one table as “one source of truth” we are creating different datasets fit for purpose: one for historical descriptions and reporting and another for relevant predictions.

- ⚠️ You might be wondering why we didn’t do this upstream in our

- Create new confidence features for drivers and constructors

- Generate flags for the constructors and drivers that were active in 2020

- We’re first referencing our upstream

-

Execute the following in the command bar:

dbt run --select ml_data_prep -

There are more aspects we could consider for this project, such as normalizing the driver confidence by the number of races entered. Including this would help account for a driver’s history and consider whether they are a new or long-time driver. We’re going to keep it simple for now, but these are some of the ways we can expand and improve our machine learning dbt projects. Breaking down our machine learning prep model:

- Lambda functions — We use some lambda functions to transform our data without having to create a fully-fledged function using the

defnotation. So what exactly are lambda functions?- In Python, a lambda function is a small, anonymous function defined using the keyword "lambda". Lambda functions are used to perform a quick operation, such as a mathematical calculation or a transformation on a list of elements. They are often used in conjunction with higher-order functions, such as

apply,map,filter, andreduce.

- In Python, a lambda function is a small, anonymous function defined using the keyword "lambda". Lambda functions are used to perform a quick operation, such as a mathematical calculation or a transformation on a list of elements. They are often used in conjunction with higher-order functions, such as

.apply()method — We used.apply()to pass our functions into our lambda expressions to the columns and perform this multiple times in our code. Let’s explain apply a little more:- The

.apply()function in the pandas library is used to apply a function to a specified axis of a DataFrame or a Series. In our case the function we used was our lambda function! - The

.apply()function takes two arguments: the first is the function to be applied, and the second is the axis along which the function should be applied. The axis can be specified as 0 for rows or 1 for columns. We are using the default value of 0 so we aren’t explicitly writing it in the code. This means that the function will be applied to each row of the DataFrame or Series.

- The

- Lambda functions — We use some lambda functions to transform our data without having to create a fully-fledged function using the

-

Let’s look at the preview of our clean dataframe after running our

ml_data_prepmodel:

Covariate encoding

In this next part, we’ll be performing covariate encoding. Breaking down this phrase a bit, a covariate is a variable that is relevant to the outcome of a study or experiment, and encoding refers to the process of converting data (such as text or categorical variables) into a numerical format that can be used as input for a model. This is necessary because most machine learning algorithms can only work with numerical data. Algorithms don’t speak languages, have eyes to see images, etc. so we encode our data into numbers so algorithms can perform tasks by using calculations they otherwise couldn’t.

🧠 We’ll think about this as : “algorithms like numbers”.

-

Create a new file under

ml/prepcalledcovariate_encodingcopy the code below and save.import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler,LabelEncoder,OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

def model(dbt, session):

# dbt configuration

dbt.config(packages=["pandas","numpy","scikit-learn"])

# get upstream data

data = dbt.ref("ml_data_prep").to_pandas()

# list out covariates we want to use in addition to outcome variable we are modeling - position

covariates = data[['RACE_YEAR','CIRCUIT_NAME','GRID','CONSTRUCTOR_NAME','DRIVER','DRIVERS_AGE_YEARS','DRIVER_CONFIDENCE','CONSTRUCTOR_RELAIBLITY','TOTAL_PIT_STOPS_PER_RACE','ACTIVE_DRIVER','ACTIVE_CONSTRUCTOR', 'POSITION']]

# filter covariates on active drivers and constructors

# use fil_cov as short for "filtered_covariates"

fil_cov = covariates[(covariates['ACTIVE_DRIVER']==1)&(covariates['ACTIVE_CONSTRUCTOR']==1)]

# Encode categorical variables using LabelEncoder

# TODO: we'll update this to both ohe in the future for non-ordinal variables!

le = LabelEncoder()

fil_cov['CIRCUIT_NAME'] = le.fit_transform(fil_cov['CIRCUIT_NAME'])

fil_cov['CONSTRUCTOR_NAME'] = le.fit_transform(fil_cov['CONSTRUCTOR_NAME'])

fil_cov['DRIVER'] = le.fit_transform(fil_cov['DRIVER'])

fil_cov['TOTAL_PIT_STOPS_PER_RACE'] = le.fit_transform(fil_cov['TOTAL_PIT_STOPS_PER_RACE'])

# Simply target variable "position" to represent 3 meaningful categories in Formula1

# 1. Podium position 2. Points for team 3. Nothing - no podium or points!

def position_index(x):

if x<4:

return 1

if x>10:

return 3

else :

return 2

# we are dropping the columns that we filtered on in addition to our training variable

encoded_data = fil_cov.drop(['ACTIVE_DRIVER','ACTIVE_CONSTRUCTOR'],axis=1))

encoded_data['POSITION_LABEL']= encoded_data['POSITION'].apply(lambda x: position_index(x))

encoded_data_grouped_target = encoded_data.drop(['POSITION'],axis=1))

return encoded_data_grouped_target -

Execute the following in the command bar:

dbt run --select covariate_encoding -

In this code, we are using a ton of functions from libraries! This is really cool, because we can utilize code other people have developed and bring it into our project simply by using the

importfunction. Scikit-learn, “sklearn” for short, is an extremely popular data science library. Sklearn contains a wide range of machine learning techniques, including supervised and unsupervised learning algorithms, feature scaling and imputation, as well as tools model evaluation and selection. We’ll be using Sklearn for both preparing our covariates and creating models (our next section). -

Our dataset is pretty small data so we are good to use pandas and

sklearn. If you have larger data for your own project in mind, considerdaskorcategory_encoders. -

Breaking it down a bit more:

- We’re selecting a subset of variables that will be used as predictors for a driver’s position.

- Filter the dataset to only include rows using the active driver and constructor flags we created in the last step.

- The next step is to use the

LabelEncoderfrom scikit-learn to convert the categorical variablesCIRCUIT_NAME,CONSTRUCTOR_NAME,DRIVER, andTOTAL_PIT_STOPS_PER_RACEinto numerical values. - Create a new variable called

POSITION_LABEL, which is a derived from our position variable.- 💭 Why are we changing our position variable? There are 20 total positions in Formula 1 and we are grouping them together to simplify the classification and improve performance. We also want to demonstrate you can create a new function within your dbt model!

- Our new

position_labelvariable has meaning:- In Formula1 if you are in:

- Top 3 you get a “podium” position

- Top 10 you gain points that add to your overall season total

- Below top 10 you get no points!

- In Formula1 if you are in:

- We are mapping our original variable position to

position_labelto the corresponding places above to 1,2, and 3 respectively.

- Drop the active driver and constructor flags since they were filter criteria and additionally drop our original position variable.

Splitting into training and testing datasets

Now that we’ve cleaned and encoded our data, we are going to further split in by time. In this step, we will create dataframes to use for training and prediction. We’ll be creating two dataframes 1) using data from 2010-2019 for training, and 2) data from 2020 for new prediction inferences. We’ll create variables called start_year and end_year so we aren’t filtering on hardcasted values (and can more easily swap them out in the future if we want to retrain our model on different timeframes).

-

Create a file called

train_test_dataset.pycopy and save the following code:import pandas as pd

def model(dbt, session):

# dbt configuration

dbt.config(packages=["pandas"], tags="train")

# get upstream data

encoding = dbt.ref("covariate_encoding").to_pandas()

# provide years so we do not hardcode dates in filter command

start_year=2010

end_year=2019

# describe the data for a full decade

train_test_dataset = encoding.loc[encoding['RACE_YEAR'].between(start_year, end_year)]

return train_test_dataset -

Create a file called

hold_out_dataset_for_prediction.pycopy and save the following code below. Now we’ll have a dataset with only the year 2020 that we’ll keep as a hold out set that we are going to use similar to a deployment use case.import pandas as pd

def model(dbt, session):

# dbt configuration

dbt.config(packages=["pandas"], tags="predict")

# get upstream data

encoding = dbt.ref("covariate_encoding").to_pandas()

# variable for year instead of hardcoding it

year=2020

# filter the data based on the specified year

hold_out_dataset = encoding.loc[encoding['RACE_YEAR'] == year]

return hold_out_dataset -

Execute the following in the command bar:

dbt run --select train_test_dataset hold_out_dataset_for_predictionTo run our temporal data split models, we can use this syntax in the command line to run them both at once. Make sure you use a space syntax between the model names to indicate you want to run both!

-

Commit and push our changes to keep saving our work as we go using

ml data prep and splitsbefore moving on.

👏 Now that we’ve finished our machine learning prep work we can move onto the fun part — training and prediction!

Training a model to predict in machine learning

We’re ready to start training a model to predict the driver’s position. Now is a good time to pause and take a step back and say, usually in ML projects you’ll try multiple algorithms during development and use an evaluation method such as cross validation to determine which algorithm to use. You can definitely do this in your dbt project, but for the content of this lab we’ll have decided on using a logistic regression to predict position (we actually tried some other algorithms using cross validation outside of this lab such as k-nearest neighbors and a support vector classifier but that didn’t perform as well as the logistic regression and a decision tree that overfit).

There are 3 areas to break down as we go since we are working at the intersection all within one model file:

- Machine Learning

- Snowflake and Snowpark

- dbt Python models

If you haven’t seen code like this before or use joblib files to save machine learning models, we’ll be going over them at a high level and you can explore the links for more technical in-depth along the way! Because Snowflake and dbt have abstracted away a lot of the nitty gritty about serialization and storing our model object to be called again, we won’t go into too much detail here. There’s a lot going on here so take it at your pace!

Training and saving a machine learning model

-

Project organization remains key, so let’s make a new subfolder called

train_predictunder themlfolder. -

Now create a new file called

train_test_position.pyand copy and save the following code:import snowflake.snowpark.functions as F

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, balanced_accuracy_score

import io

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from joblib import dump, load

import joblib

import logging

import sys

from joblib import dump, load

logger = logging.getLogger("mylog")

def save_file(session, model, path, dest_filename):

input_stream = io.BytesIO()

joblib.dump(model, input_stream)

session._conn.upload_stream(input_stream, path, dest_filename)

return "successfully created file: " + path

def model(dbt, session):

dbt.config(

packages = ['numpy','scikit-learn','pandas','numpy','joblib','cachetools'],

materialized = "table",

tags = "train"

)

# Create a stage in Snowflake to save our model file

session.sql('create or replace stage MODELSTAGE').collect()

#session._use_scoped_temp_objects = False

version = "1.0"

logger.info('Model training version: ' + version)

# read in our training and testing upstream dataset

test_train_df = dbt.ref("train_test_dataset")

# cast snowpark df to pandas df

test_train_pd_df = test_train_df.to_pandas()

target_col = "POSITION_LABEL"

# split out covariate predictors, x, from our target column position_label, y.

split_X = test_train_pd_df.drop([target_col], axis=1)

split_y = test_train_pd_df[target_col]

# Split out our training and test data into proportions

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(split_X, split_y, train_size=0.7, random_state=42)

train = [X_train, y_train]

test = [X_test, y_test]

# now we are only training our one model to deploy

# we are keeping the focus on the workflows and not algorithms for this lab!

model = LogisticRegression()

# fit the preprocessing pipeline and the model together

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = model.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

predictions = [round(value) for value in y_pred]

balanced_accuracy = balanced_accuracy_score(y_test, predictions)

# Save the model to a stage

save_file(session, model, "@MODELSTAGE/driver_position_"+version, "driver_position_"+version+".joblib" )

logger.info('Model artifact:' + "@MODELSTAGE/driver_position_"+version+".joblib")

# Take our pandas training and testing dataframes and put them back into snowpark dataframes

snowpark_train_df = session.write_pandas(pd.concat(train, axis=1, join='inner'), "train_table", auto_create_table=True, create_temp_table=True)

snowpark_test_df = session.write_pandas(pd.concat(test, axis=1, join='inner'), "test_table", auto_create_table=True, create_temp_table=True)

# Union our training and testing data together and add a column indicating train vs test rows

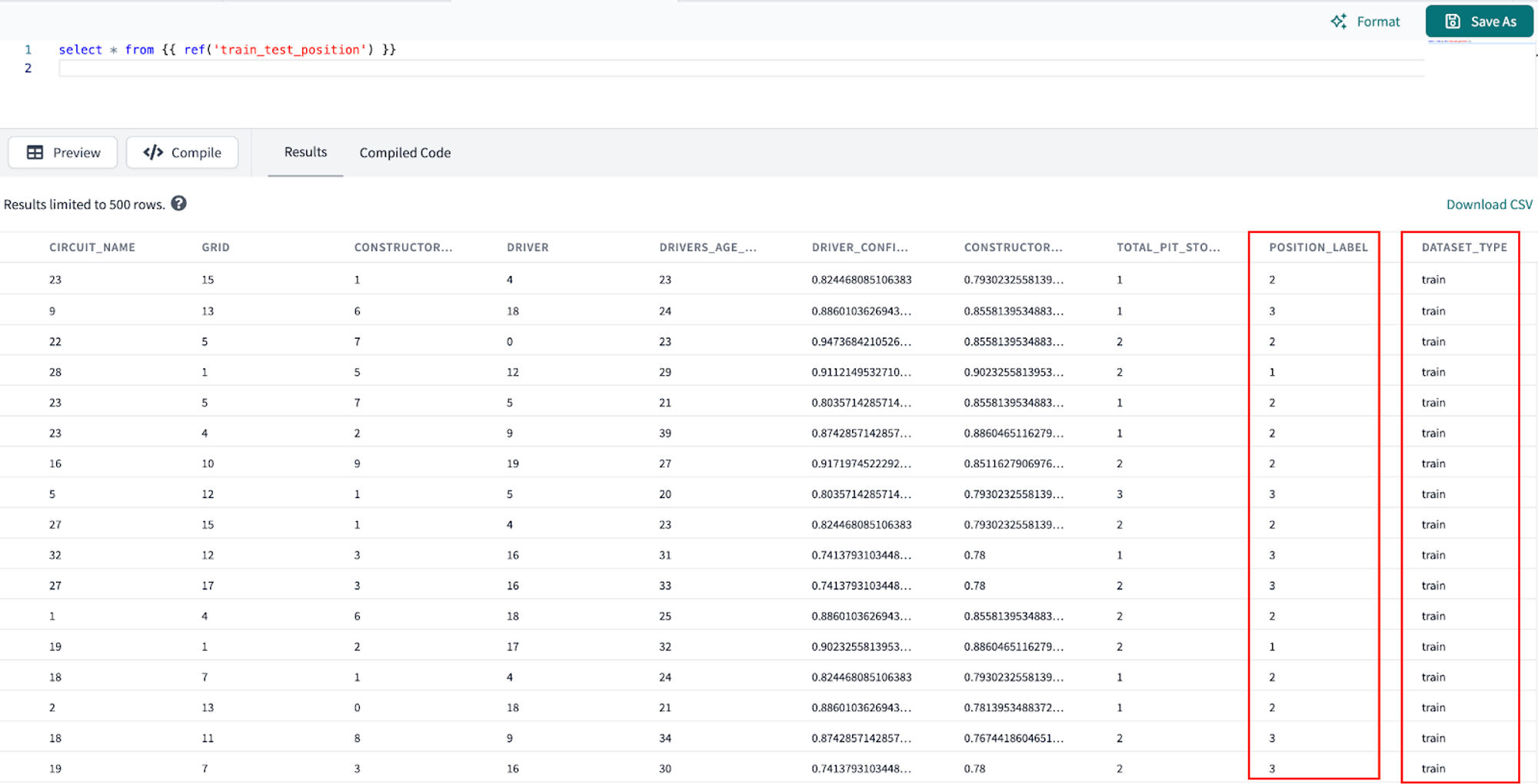

return snowpark_train_df.with_column("DATASET_TYPE", F.lit("train")).union(snowpark_test_df.with_column("DATASET_TYPE", F.lit("test"))) -

Execute the following in the command bar:

dbt run --select train_test_position -

Breaking down our Python script here:

- We’re importing some helpful libraries.

- Defining a function called

save_file()that takes four parameters:session,model,pathanddest_filenamethat will save our logistic regression model file.session— an object representing a connection to Snowflake.model— an object that needs to be saved. In this case, it's a Python object that is a scikit-learn that can be serialized with joblib.path— a string representing the directory or bucket location where the file should be saved.dest_filename— a string representing the desired name of the file.

- Creating our dbt model

- Within this model we are creating a stage called

MODELSTAGEto place our logistic regressionjoblibmodel file. This is really important since we need a place to keep our model to reuse and want to ensure it's there. When using Snowpark commands, it's common to see the.collect()method to ensure the action is performed. Think of the session as our “start” and collect as our “end” when working with Snowpark (you can use other ending methods other than collect). - Using

.ref()to connect into ourtrain_test_datasetmodel. - Now we see the machine learning part of our analysis:

- Create new dataframes for our prediction features from our target variable

position_label. - Split our dataset into 70% training (and 30% testing), train_size=0.7 with a

random_statespecified to have repeatable results. - Specify our model is a logistic regression.

- Fit our model. In a logistic regression this means finding the coefficients that will give the least classification error.

- Round our predictions to the nearest integer since logistic regression creates a probability between for each class and calculate a balanced accuracy to account for imbalances in the target variable.

- Create new dataframes for our prediction features from our target variable

- Within this model we are creating a stage called

- Right now our model is only in memory, so we need to use our nifty function

save_fileto save our model file to our Snowflake stage. We save our model as a joblib file so Snowpark can easily call this model object back to create predictions. We really don’t need to know much else as a data practitioner unless we want to. It’s worth noting that joblib files aren’t able to be queried directly by SQL. To do this, we would need to transform the joblib file to an SQL querable format such as JSON or CSV (out of scope for this workshop). - Finally we want to return our dataframe, but create a new column indicating what rows were used for training and those for training.

- Defining a function called

- We’re importing some helpful libraries.

-

Viewing our output of this model:

-

Let’s pop back over to Snowflake and check that our logistic regression model has been stored in our

MODELSTAGEusing the command:list @modelstage

List the objects in our Snowflake stage to check for our logistic regression to predict driver position

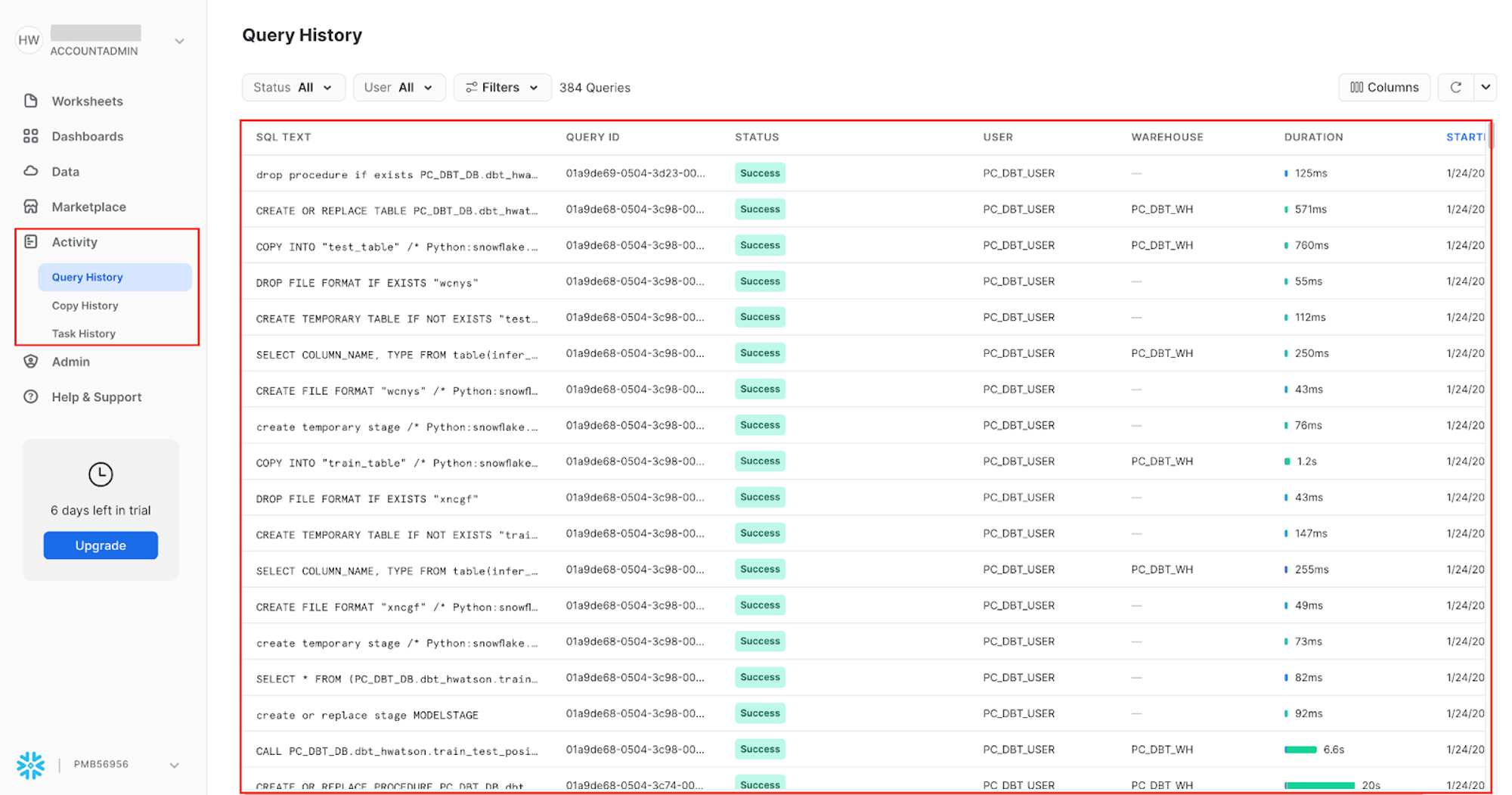

List the objects in our Snowflake stage to check for our logistic regression to predict driver position- To investigate the commands run as part of

train_test_positionscript, navigate to Snowflake query history to view it Activity > Query History. We can view the portions of query that we wrote such ascreate or replace stage MODELSTAGE, but we also see additional queries that Snowflake uses to interpret python code.

Predicting on new data

-

Create a new file called

predict_position.pyand copy and save the following code:import logging

import joblib

import pandas as pd

import os

from snowflake.snowpark import types as T

DB_STAGE = 'MODELSTAGE'

version = '1.0'

# The name of the model file

model_file_path = 'driver_position_'+version

model_file_packaged = 'driver_position_'+version+'.joblib'