Incremental models in-depth

So far we’ve looked at tables and views, which map to the traditional objects in the data warehouse. As mentioned earlier, incremental models are a little different. This is where we start to deviate from this pattern with more powerful and complex materializations.

- 📚 Incremental models generate tables. They physically persist the data itself to the warehouse, just piece by piece. What’s different is how we build that table.

- 💅 Only apply our transformations to rows of data with new or updated information, this maximizes efficiency.

- 🌍 If we have a very large set of data or compute-intensive transformations, or both, it can be very slow and costly to process the entire corpus of source data being input into a model or chain of models. If instead we can identify only rows that contain new information (that is, new or updated records), we then can process just those rows, building our models incrementally.

- 3️⃣ We need 3 key things in order to accomplish the above:

- a filter to select just the new or updated records

- a conditional block that wraps our filter and only applies it when we want it

- configuration that tells dbt we want to build incrementally and helps apply the conditional filter when needed

Let’s dig into how exactly we can do that in dbt. Let’s say we have an orders table that looks like the below:

| Loading table... |

We did our last dbt build job on 2022-01-31, so any new orders since that run won’t appear in our table. When we do our next run (for simplicity let’s say the next day, although for an orders model we’d more realistically run this hourly), we have two options:

- 🏔️ build the table from the beginning of time again — a table materialization

- Simple and solid, if we can afford to do it (in terms of time, compute, and money — which are all directly correlated in a cloud warehouse). It’s the easiest and most accurate option.

- 🤏 find a way to run just new and updated rows since our previous run — an incremental materialization

- If we can’t realistically afford to run the whole table — due to complex transformations or big source data, it takes too long — then we want to build incrementally. We want to just transform and add the row with id 567 below, not the previous two with ids 123 and 234 that are already in the table.

| Loading table... |

Writing incremental logic

Let’s think through the information we’d need to build such a model that only processes new and updated data. We would need:

- 🕜 a timestamp indicating when a record was last updated, let’s call it our

updated_attimestamp, as that’s a typical convention and what we have in our example above. - ⌛ the most recent timestamp from this table in our warehouse — that is, the one created by the previous run — to act as a cutoff point. We’ll call the model we’re working in

this, for ‘this model we’re working in’.

That would lets us construct logic like this:

select * from orders

where

updated_at > (select max(updated_at) from {{ this }})

Let’s break down that where clause a bit, because this is where the action is with incremental models. Stepping through the code right-to-left we:

- Get our cutoff.

- Select the

max(updated_at)timestamp — the most recent record - from

{{ this }}— the table for this model as it exists in the warehouse, as built in our last run, - so

max(updated_at) from {{ this }}the most recent record processed in our last run, - that’s exactly what we want as a cutoff!

- Select the

- Filter the rows we’re selecting to add in this run.

- Use the

updated_attimestamp from our input, the equivalent column to the one in the warehouse, but in the up-to-the-minute source data we’re selecting from and - check if it’s greater than our cutoff,

- if so it will satisfy our where clause, so we’re selecting all the rows more recent than our cutoff.

- Use the

This logic would let us isolate and apply our transformations to just the records that have come in since our last run, and I’ve got some great news: that magic {{ this }} keyword does in fact exist in dbt, so we can write exactly this logic in our models.

Configuring incremental models

So we’ve found a way to isolate the new rows we need to process. How then do we handle the rest? We still need to:

- ➕ make sure dbt knows to add new rows on top of the existing table in the warehouse, not replace it.

- 👉 If there are updated rows, we need a way for dbt to know which rows to update.

- 🌍 Lastly, if we’re building into a new environment and there’s no previous run to reference, or we need to build the model from scratch. Put another way, we’ll want a means to skip the incremental logic and transform all of our input data like a regular table if needed.

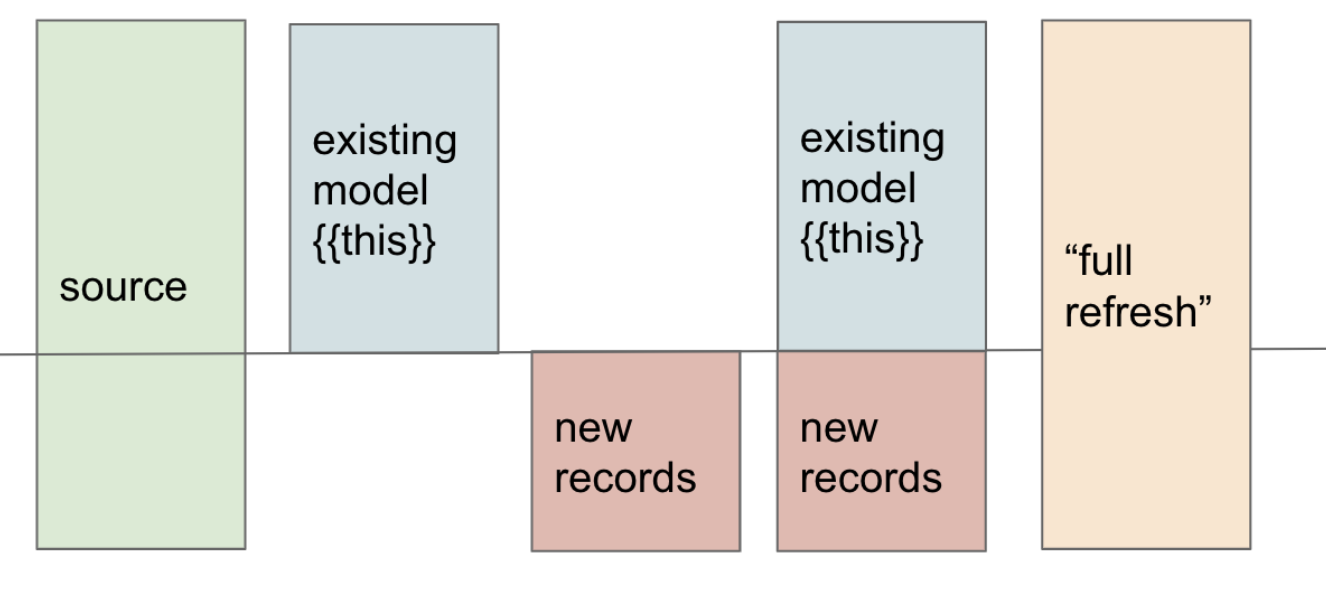

- 😎 Visualized below, we’ve figured out how to get the red ‘new records’ portion selected, but we need to sort out the step to the right, where we stick those on to our model.

😌 Incremental models can be confusing at first, take your time reviewing this visual and the previous steps until you have a clear mental model. Be patient with yourself. This materialization will become second nature soon, but it’s tough at first. If you’re feeling confused the dbt Community is here for you on the Forum and Slack.

Thankfully dbt has some additional configuration and special syntax just for incremental models.

First, let's look at a config block for incremental materialization:

{{

config(

materialized='incremental',

unique_key='order_id'

)

}}

select ...

- 📚 The

materializedconfig works just like tables and views, we just pass it the value'incremental'. - 🔑 We’ve added a new config option

unique_key, that tells dbt that if it finds a record in our previous run — the data in the warehouse already — with the same unique id (in our caseorder_idfor ourorderstable) that exists in the new data we’re adding incrementally, to update that record instead of adding it as a separate row. - 👯 This hugely broadens the types of data we can build incrementally from just immutable tables (data where rows only ever get added, never updated) to mutable records (where rows might change over time). As long as we’ve got a column that specifies when records were updated (such as

updated_atin our example), we can handle almost anything. - ➕ We’re now adding records to the table and updating existing rows. That’s 2 of 3 concerns.

- 🆕 We still need to build the table from scratch (via

dbt buildorrunin a job) when necessary — whether because we’re in a new environment so don’t have an initial table to build on, or our model has drifted from the original over time due to data loading latency. - 🔀 We need to wrap our incremental logic, that is our

whereclause with ourupdated_atcutoff, in a conditional statement that will only apply it when certain conditions are met. If you’re thinking this is a case for a Jinja{% if %}statement, you’re absolutely right!

Incremental conditions

So we’re going to use an if statement to apply our cutoff filter only when certain conditions are met. We want to apply our cutoff filter if the following things are true:

- ➕ we’ve set the materialization config to incremental,

- 🛠️ there is an existing table for this model in the warehouse to build on,

- 🙅♀️ and the

--full-refreshflag was not passed.- full refresh is a configuration and flag that is specifically designed to let us override the incremental materialization and build a table from scratch again.

Thankfully, we don’t have to dig into the guts of dbt to sort out each of these conditions individually.

- ⚙️ dbt provides us with a macro

is_incrementalthat checks all of these conditions for this exact use case. - 🔀 By wrapping our cutoff logic in this macro, it will only get applied when the macro returns true for all of the above conditions.

Let’s take a look at all these pieces together:

{{

config(

materialized='incremental',

unique_key='order_id'

)

}}

select * from orders

{% if is_incremental() %}

where

updated_at > (select max(updated_at) from {{ this }})

{% endif %}

Fantastic! We’ve got a working incremental model. On our first run, when there is no corresponding table in the warehouse, is_incremental will evaluate to false and we’ll capture the entire table. On subsequent runs it will evaluate to true and we’ll apply our filter logic, capturing only the newer data.

Late-arriving facts

Our last concern specific to incremental models is what to do when data is inevitably loaded in a less-than-perfect way. Sometimes data loaders will, for a variety of reasons, load data late. Either an entire load comes in late, or some rows come in on a load after those with which they should have. The following is best practice for every incremental model to slow down the drift this can cause.

- 🕐 For example if most of our records for

2022-01-30come in the raw schema of our warehouse on the morning of2022-01-31, but a handful don’t get loaded til2022-02-02, how might we tackle that? There will already bemax(updated_at)timestamps of2022-01-31in the warehouse, filtering out those late records. They’ll never make it to our model. - 🪟 To mitigate this, we can add a lookback window to our cutoff point. By subtracting a few days from the

max(updated_at), we would capture any late data within the window of what we subtracted. - 👯 As long as we have a

unique_keydefined in our config, we’ll simply update existing rows and avoid duplication. We process more data this way, but in a fixed way, and it keeps our model hewing closer to the source data.

Using state-aware orchestration with incremental models

By default, state-aware orchestration detects source freshness by checking warehouse metadata for any new rows. This may cause models to run more often than needed.

To avoid this issue, configure a loaded_at_field for a specific timestamp column or use a loaded_at_query with custom SQL to tell dbt which field to check for freshness. This helps state-aware orchestration to detect only genuinely new data. For information on how to configure loaded_at_field and loaded_at_query, refer to Source freshness and Advanced configurations.

Even with a loaded_at_field or loaded_at_query, late arriving records may have an earlier event timestamp (for example, event_date). In this case, state-aware orchestration may skip rebuilding the incremental model, even though your lookback window would normally pick up those records. To ensure late-arriving data is detected, configure your loaded_at_query to align with the same lookback window used in your incremental filter. For example, if your incremental model uses a 3-day lookback window:

sources:

- name: raw_orders

tables:

- name: orders

config:

loaded_at_query: |

select max(ingested_at)

from {{ this }}

where ingested_at >= current_timestamp - interval '3 days'

Long-term considerations

Late arriving facts point to the biggest tradeoff with incremental models:

- 🪢 In addition to extra complexity, they also inevitably drift from the source data over time. Due to the imperfection of loaders and the reality of late arriving facts, we can’t help but miss some day in-between our incremental runs, and this accumulates.

- 🪟 We can slow this entropy with the lookback window described above — the longer the window the less efficient the model, but the slower the drift. It’s important to note it will still occur though, however slowly. If we have a lookback window of 3 days, and a record comes in 4 days late from the loader, we’re still going to miss it.

- 🌍 Thankfully, there is a way we can reset the relationship of the model to the source data. We can run the model with the

--full-refreshflag passed (such asdbt build --full-refresh -s orders). As we saw in theis_incrementalconditions above, that will make our logic return false, and ourwhereclause filter will not be applied, running the whole table. - 🏗️ This will let us rebuild the entire table from scratch, a good practice to do regularly if the size of the data will allow.

- 📆 A common pattern for incremental models of manageable size is to run a full refresh on the weekend (or any low point in activity), either weekly or monthly, to consistently reset the drift from late arriving facts.

Was this page helpful?

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.